Hurricane Iniki was a pivotal event in my life. It crystalized and made real a belief that I had that amateur radio plays a vital and irreplacable part prior to and immediately after of such a large scale event, orchestrating joint operations and recovery.

After years of preparation, a hurricane came suddenly upon Hawaii and caused destruction and disruption of a magnitude unseen in modern times. The behind-the-scenes teamwork of a number of agencies and individuals convinced me and demonstrated that emergency communications using amateur radio is vital and essential, and that as amateur radio operators, we should be ready to serve.

Enjoy, and feel free to drop me an e-mail if you have any questions.

This is an article that originally appeared in the February 1993 edition of amateur radio's national journal, the American Radio Relay League's QST, pages 19-22.

Copyright © 1993 ARRL (American Radio Relay League, Inc.)

By Ron Hashiro, KH6JCA (Now AH6RH)

As Hurricane Iniki tore its destruction through the Hawaiian Islands, Amateur Radio operators maintained an exclusive communications backbone.

On Friday, September 11, 1992, Hurricane Iniki slammed into the Hawaiian island of Kauai, the northwestern-most of the path of Hawaiian Islands chain. In a matter of hours, the 51,000 residents experienced the effects of 165-mi/h winds. More than 8000 people became homeless when 7000 homes were destroyed or severely damaged. The Category 4 storm caused an estimated $1.6 billion in insured losses and left 6500 people without jobs.

As the winds whipped across the mountaintops, microwave dishes warped and radio towers fell. Phone service began to fail. By midafternoon, as the storm passed, Kauai residents could no longer make long-distance telephone calls. Amateur Radio became the only direct link between Kauai and Oahu, the closest neighboring island. Hams relayed early messages that would jump-start emergency operations and set the stage for the growing relief efforts.

From start to finish, Kauai amateurs banded together on the radio and behind the scenes, putting on an incredible display of operating skill.

The Setting

Public service has always been one of the cornerstones of Amateur Radio. The Radio Amateur Civil Emergency Service (RACES) was created as a means for radio amateurs to serve civil defense agencies during times of war and disaster. The RACES program for the Hawaii State Civil Defense (SCD) had been dormant for several years until Robin Liu, AH6CP, began talks with SCD in 1985 to reactivate Amateur Radio participation in the state's Civil Defense plans. The first fruit of his effort enabled a team of hams led by Liu to build an emergency VHF repeater network spanning the various islands.

| [PHOTO: Leaning utility poles on Kauai are a reminder of the strength of Hurricane lniki's winds. In many instances electrical cables snapped and, while the telephone wiring remained intact, allowing intra-island phone service, there was no phone connection into or out of the island. (photo by KH6JCA)] |

Visitors to Hawaii often use the Hawaii State RACES system. The four-repeater system consists of repeaters on Diamond Head, Oahu; on Mt Haleakala, Maui; on Mauna Loa, the Big Island; and in Lihue, Kauai. In addition, a series of packet digipeaters on 2 meters had been installed by Hal Sprague, KH6GPI, and Robin Liu, spurring additional growth and interest in state-wide packet radio operations.

| Photo: [David Rudawitz, N6QXQ, a Red Cross volunteer from Anaheim, California, supervises damage assessment at Poipu Beach. Rudawitz, who arrived on Kauai four days after Iniki struck, found that Red Cross point-to-point communications were being handled by amateurs-who were in "very short supply"- on 2 meters and immediately put his handheld to good use. Rudawitz was able to meet the Red Cross requirement of committing to a three-week assignment. (photo by Tim Robinson)] |

Throughout the week, Hurricane Iniki had traveled south of the Hawaiian Islands along a northwesterly path. By Thursday, the storm had turned northward and was headed straight for Kauai. Despite the 80 miles of ocean separating Kauai from the main island of Oahu, storm warnings were posted for both islands. That evening, AH6CP activated the state RACES station, KH6HPZ, from the Emergency Operating Center (EOC) located in Burkheimer Tunnel within the crater at Diamond Head. AH6CP passed out the latest information on the hurricane and other preparations. Net operations were secured at 11 PM, to resume at 5:30 the next morning.

Cliff Ikeda, NH6HF, the Civil Defense Communications Officer for Kauai County, was on Oahu for a series of meetings. He was dining at a restaurant when he received a call from Kauai Mayor JoAnn Yukimura indicating that Iniki had turned toward Kauai and to report to the airport immediately for a return flight.

Friday Morning

The author resumed the state RACES net at 5:30 AM as Oahu and Kauai residents awoke to emergency sirens and immediately tuned to broadcast stations for the latest official bulletins. All non-essential workers were advised to stay home. In moments, the telephone systems on Oahu and Kauai were jammed by a flood of phone calls as workers frantically tried to contact their workplaces. Undisturbed by the frenzy, Amateur Radio operators continued to prepare and provide inter-island communications.

From his office at the National Weather Service at Honolulu International Airport, forecaster Mike Morrow, KH6JQM, activated the SKYWARN radio net. He was soon joined by Ronald Henry, N9KWW, and Bill Stookey, WH6EL. SKYWARN participants collected weather observations from hams and relayed the latest weather analysis. When the NOAA radio failed later that day, SKYWARN turned to Amateur Radio.

At the Kauai EOC - in the basement of the County Building in Lihue, Kauai's main town - Communications Officer Ikeda devoted himself to emergency preparation meetings with Mayor Yukimura and her staff, pausing only to brief state Civil Defense officials via amateur VHF radio. Robbie Reneau, KH6JIV, also in Lihue, passed timely reports via the RACES VHF repeater system to Robin Liu, AH6CP, and Pat Corrigan, KH6DD, at SCD in Honolulu.

| Photo: [Hawaii state RACES coordinator Robin Liu, AH6CP, pauses from his work at Civil Defense Headquarters in Honolulu just before the peak of lniki. Liu, a Motorola project engineer, left shortly thereafter for Kauai, where he spent almost 36 hours directing Motorola radio technicians and aiding Kauai County Civil Defense. (photo by KH6JCA)] |

The author returned to the state EOC at 2 PM with a VHF packet station from his home, and KH6DD, at the Honolulu SCD, switched to packet to begin receiving electronic messages through a PacketCluster node on Oahu operated by Ron McMurdy, WA0OJS.

At 3:04 PM, telephone service out of Kauai was lost and government radio had failed. Shortly after that, the NH6HF RACES repeater on Kauai went down, and voice operations switched to the Hawaiian Tel Amateur Radio repeater, KH6JPL, located on Oahu's Waianae mountain range. This 2-meter repeater covers most of Oahu and -thankfully-parts of Kauai.

As the storm pressed on, the news media on Oahu reported only that "Ham radio operators are in touch with Kauai, but we have no additional word on damage or other status." With services knocked out and people huddling in shelters and homes, reports were few and far between.

Safe within the basement of the Kauai County Building, which was running on internally generated power, NH6HF's VHF voice and packet radios became the last remaining links from Kauai. Liu apprised Ikeda of the latest storm position and forecast by reading National Weather Service teletype bulletins. At 4 PM, during the height of the storm, the mayor asked Ikeda to contact Governor John Waihee via Amateur Radio. Billy Gomban, KH6JPL, the Hawaiian Tel ARC repeater trustee, offered the use of the repeater's telephone autopatch. Liu obtained the repeater's control codes from Gomban and initiated the repeater's reverse autopatchfor the governor.

Governor Waihee assured the mayor that relief materials and federal aid were coming. Without firm damage reports, but judging from the flying debris, Mayor Yukimura observed that damage was extensive and listed the items most needed. The phone patch confirmed that damage was widespread and intensified the emergency and relief response.

The author transcribed details of the phone patch onto a radio message form and gave it to state CD officials for their review. Minutes later, the governor arrived at the state EOC and was about to inform the officials of the mayor's request when he saw a complete hardcopy of the message in the officials' hands. Governor Waihee was very impressed and pleased with the speed and completeness of the Amateur Radio operations.

The Hurricane Passes

By 7:30 PM, the storm had subsided and by 10 PM, a thick, warm, humid calm had replaced the storm winds of only a few hours before.

Most of Kauai's phone service through GTE Hawaiian Telephone remained out of service with the two microwave links between Kauai and Oahu down. Limited phone service was available in the towns of Lihue and Kapaa.; Throughout the night, amateurs continued their work. Lance Cabral, WH6EE, and Robbie Reneau, KH6JIB, joined Ikeda at the Kauai EOC to coordinate the dozens of relief operations.

Road crews began clearing operations: power, water and phone service had to be restored, and the critically injured needed immediate medical attention. Two-way communications were crucial in identifying medical emergencies, locating work crews and equipment, developing action plans and establishing meeting points and schedules.

Messages began to flow between Kauai and Oahu as Kauai hams returned to the airwaves. Oahu repeaters KH6FV, KH6TB and KH6JUU began handling outbound Health-and-Welfare traffic. Ray Nawrocki, NH6RZ, used his 11-element beam and 45 watts to "brute force" his signal from Mililani, on Oahu, through the Waianae mountains into Kauai. A couple of Kauai hams also reestablished operations on FM.

By now, hundreds of Health-and-Welfare messages had poured into Hawaii on HF packet. Oahu amateurs began holding this inbound traffic as most of the telephones were out and virtually every Kauai ham had more immediate situations to attend to. Since all Kauai broadcast stations were off the air, Kauai officials turned to Oahu's KSSK-AM for information. The author used VHF FM to patch Kauai officials to KSSK for a live radio announcement, to update residents and give the order to transport critical patients to the nearest fire station.

Preparations for airlifts into Lihue continued through the night. Although the runway was clear and the marker lights worked, the control tower was damaged and out of commission. Without radio navigation aids, the decision was made to commence helicopter and C-130 airlifts in the morning "at first light." Shortly after midnight, the Lihue airport manager closed the airport to scheduled commercial air traffic until Monday morning.

Flying to Kauai

Several hams were among the first relief workers to fly to Kauai following the hurricane. Motorola repair technicians Robin Liu, AH6CP, and Tom Simon, NH6XP, flew on a Chinook military helicopter, while George Hanzawa, KH6JUU, flew aboard a Hawaii Air Ambulance plane. They joined with technician Neil Iseri, NH6FJ, to restore the government radio system.

Hawaiian Tel engineer Vince Soeda, NH6KW, left on another helicopter to lead the restoration of the inter-island microwave system. Oahu's KH6JPL repeater became a vital part of Hawaiian Tel's restoration effort, linking NH6KW with Hawaiian Tel's recovery command center. Among the Hawaiian Tel hams operating through the KH6JPL repeater were Billy Gomban, KH6JPL; Pat Chu, KH6KL; Francis Button, NH6JY; and Mike Scott, N6GOZ.

| Photo: [Vince Soeda, NH6KW, an engineer for GTE Hawaiian Telephone, pauses briefly next to a portable microwave system on Kauai. Soeda, one of the first Hawaiian Tel engineers to arrive on Kauai following the storm, used his hand-held to patch through to the phone company emergency operating center, using Hawaiian Tel's Amateur Radio Club VHF repeater on Oahu. 2 meters was then used to coordinate realignment of the telephone company's dish antennas. (photo courtesy of Vince Soeda, NH6KW)] |

Hawaiian Tel engineer Soeda contacted the Oahu technicians via KH6JPL and directed the realignment of the microwave antenna dishes. Some paths had suffered a 20 dB loss in signal strength. Tests showed that the seemingly minor physical damage had radically reduced antenna gains and that initial repairs had to be on a "best effort" basis.

With the Lihue airport tower radio out of commission, FAA radio engineer Dan Miyashiro, AH6IM, arrived on Kauai on Tuesday to restore repeater service for the Federal Aviation Administration.

AH6CP and other Motorola technicians managed to repair the government radios and antennas, but were hampered by lack of electrical power. AH6CP filled in for NH6HF at the Kauai EOC while waiting for generators to arrive from Oahu.

By Saturday morning, radio operators at EOCs on Kauai and in Honolulu were exhausted. A call went out by Amateur Radio for volunteers. John Fulmer, WT6M, and Lawrence Koga, NH6NJ, relieved the state EOC operators while Bill Stookey, WH6EL, and Joann Hosanny, WH6CF, flew to Kauai to replace the Kauai EOC operators. The EOC operators had handled more than 50 official messages and hundreds of informal messages and phone patches.

Volunteers for Kauai had to bring their own provisions and had to be prepared to stay for an indefinite time. Joe Keola, KH6BFZ, and Jeep Briones, WH6CEN, went with ready-to-operate VHF and HF stations complete with generators and food provisions. Requesting the most difficult assignment, they were sent to the evacuation shelter at Koloa Elementary School, near the Poipu Beach resort area, where more than 750 tourists were stranded without any means of communications.

Keola and Briones arrived at 3:30 PM Sunday and instructed each visitor to write the name and phone number of a friend or relative along with their names and a brief message. They set up the station within thirty minutes and passed messages to waiting Oahu hams. The Oahu hams placed collect phone calls to the loved ones, who eagerly accepted the messages. The two operators originated more than a thousand messages in six non-stop hours, completing calls as far away as Sweden.

Other emergency communications were spontaneous. San Diego visitors Jack Simmons, KI6RF, and his wife Ann left their condo and dropped in on Wilcox Hospital in Lihue. Ann, who is a nurse, began working with the administrators to organize a list of critical items. RACES volunteer Bob Hlivak, NH6XO, responded to American Red Cross headquarters on the slopes of Diamond Head crater, set up a VHF station, and worked with a Red Cross disaster official to establish a hospital net. Working through KI6RF and NH6XO, Wilcox hospital requisitioned and coordinated delivery of sterile laundry, medical personnel and pharmaceuticals from Oahu hospitals. Later, they passed a drug list through the KH6JPL repeater autopatch directly to a mainland pharmaceutical firm. NH6XO was relieved when American Red Cross amateurs arrived from Guam where they had been diverted from Typhoon Omar efforts.

| Photo: [A Red Cross worker uses 2 meters; Dick Atwood,KB7IO, is in the foreground. (photo by AH6J)] |

Ed Coan, AIOD, walked into the American Red Cross headquarters at Lihue and volunteered his services, along with his HF rig and VHF-UHF hand-held. Shelter management communications were established on 7.228 MHz and on two Kauai VHF repeaters. Coan's wife monitored one radio while he passed messages on the other.

Voice communication was the most flexible means of sharing a radio channel between several agencies, but the hard-copy packet messages proved most effective in directing operations.

VHF packet radio continued around the clock, but on Sunday morning, the final amplifier transistors overheated and the packet station at the State EOC could not maintain full power output. KH6DD returned home to operate packet and faxed the hard copy messages to the EOC. Phone service between Kauai and Oahu returned on Sunday evening, although only the residents of Lihue and Kapaa could call out at the time. In the community interest, the phone company waived the inter-island toll charges between Kauai and the rest of Hawaii for two weeks. GTE Hawaiian Tel urged Hawaii residents to wait and allow Kauai residents to dial out. Once the initial surge of phone calls tapered off, calls began flowing into Kauai.

One of the obstacles Kauai Civil Defense officials tried to overcome was getting timely public information to the community. Jerry Wine, KH6UH, flew in Sunday morning and was assigned to link the Kauai EOC officials with Kauai radio station KQNG.; The station engineers were flown to Kauai and had managed to restore limited broadcast power. Wine setup using Amateur Radio and continued until regular phone service was restored.

Wine then traveled north toward the town of Hanalei in search of other projects. He was surprised to find these rural areas had not received any radio broadcasts and had yet to receive aid. The antenna at one of the fire stations had been damaged by flying debris. The firefighters were impressed as KH6UH fashioned a makeshift antenna and used a flattened garbage can lid as the ground plane.

Electricity remained out to almost the entire island and it was some four days before pumping stations began supplying water. Still, many people would not have electricity, water or phone service for days or weeks. Lines formed as people waited for ice to keep food from spoiling.

Peter Yuen, KH6JBS, arrived on Monday afternoon aboard a C-130 to restore data communications for the credit unions. His equipment missed the flight, so Yuen spent the night at the manager's home. That night, he noted C-130 and C-5 transports arriving every ten minutes. In the morning, Yuen received his equipment, completed the repairs, and left Tuesday afternoon. By that time, amateur traffic had died down on 2 meters.

American Red Cross volunteers David Shak, NH6LQ, and Sibyl Sur, WH6CG, were called up to staff Red Cross operations on Kauai. They arrived Tuesday afternoon, and Shak began passing traffic between the Kauai EOC and the Red Cross headquarters in Lihue.

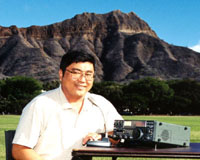

| Photo: [The author at Civil Defense Headquarters in Honolulu talks to Kauai Civil Defense shortly after Hurricane lniki's departure. (photo courtesy of KH6JCA)] |

The communications van of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) arrived from Florida and began operations by late Saturday. Incoming commercial airliners brought FEMA and other relief officials, and left with visitors returning home. The visitors in Koloa were bussed to Lihue airport and flew onto Oahu-the first leg of their return trip home. Several days later, Motorola installed and activated an 800-MHz trunking radio system for the relief agencies, and amateur activity began to wind down shortly thereafter. Phone service was restored to all Kauai central offices in about two weeks, but homes and businesses were still out of service.

Oahu and the Aftermath

On the island of Oahu, the Waianae coastline suffered extensive damage from the huge surf and Iniki's storm tides that sent waves crashing into the second floors of the beachside apartments

By Saturday afternoon, the critical patients were safely flown to Oahu. Inter-island telephone service was restored by Sunday evening and Tel engineer Soeda credits the KH6JPL repeater with shaving at least a full day off the repair job. All the ham volunteers returned safely to Oahu, exhausted but satisfied.

A videoconference of the Iniki efforts was uplinked to the ARRL Pacificon convention in Concord, California, and relayed in the San Francisco Bay area on Saturday, October 17.

Lessons Learned

The loss of the telephone system was both a challenge and a curse. The amateurs stepped in immediately and provided communications to coordinate emergency and relief efforts, yet could not handle the crushing volume of incoming Health-and-Welfare inquiries that began pouring into Hawaii.

Only a couple of VHF FM repeaters were outfitted with phone patches. More ham phone patch equipment would have made phone calls on the other repeaters easier to handle.

People from all sectors -- government, medical, business and relief agencies -- struggled to clear distribution channels for material, equipment and trained workers.

Well-composed messages greatly improved coordination of the hundreds of activities into a recovery operation. Messages containing the originator's name, organization and radio contact aided decision makers in better understanding the nature of the aid requests and offers for assistance.

One observation is that Oahu had about 10 times the population and resources of Kauai and could mobilize quickly to render aid. If Iniki had struck Oahu, the Neighbor Islands would have been hard pressed to support Oahu. Major Oahu relief would have to wait at least a week for ships from California.

Kauai's isolation hampered additional amateurs from flying onto the island. Government and relief agency officials prioritized and limited the initial number of amateurs who could participate, due to the limited number of seats and also out of concern for personal liability.

In an instant, the media and the general public became very interested in Amateur Radio. But the amateurs were so completely involved in their relief work that, consequently, they were not totally prepared during media interviews to present Amateur Radio in a concise but meaningful fashion.

The key to a successful recovery operation is establishing relationships with officials in local government, hospitals and similar public service agencies before disaster strikes. Amateurs need to educate these officials on how Amateur Radio operators can and will participate by being integrated into existing disaster preparation and relief efforts.

And officials need to understand that amateurs in their communities have already invested thousands of dollars in equipment to engage in daily radio communications and that by establishing working relationships they can tap that ready resource with little or no outlays on their part.

Amateur Radio is reliable in emergencies because the hams in the affected area can establish themselves quickly, knowing that others are waiting to pitch in and help out. Faced with tight budgets, officials welcome the comfort of additional means of disaster communications.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Robin Liu AH6CP, for his invaluable assistance in preparing this article.

A note from Bob Schneider, AH6J, Pacific Section Manager: This article was made up of a massive amount of material from many sources. Many people and group stories had to be left out because of space considerations. For example, members of the Big Island ARC went over with their portable repeater, HF equipment, packet equipment and hand- helds. Other groups, including the Emergency ARC and Koolau ARC, also made major efforts.

Ron Hashiro, 35, is a data processing officer for First Hawaiian Bank in Honolulu. During and after Hurricane Iniki's visit to the Hawaiian Islands, he volunteered first as a radio operator at the Hawaii State Civil Defense Emergency Operating Center in Honolulu, and then traveled to Kauai on business. He is an ARRL Life Member.

Reprinted with permission from February 1993 QST

Copyright © 1993 ARRL

(American Amateur Radio Relay League, Inc.)

See also:

- Star-Bulletin article: Ham radio vital link for Kauai during Iniki

- WorldRadio article: Iniki and the American Red Cross

- Hurricane Iniki Page

- Ron Hashiro, AH6RH Amateur Radio Articles Page

- Ron Hashiro, AH6RH Emergency Communications in Hawaii Page

Postscript

The devestation of a strong hurricane is so immense and widespread, that the need for help and communications will overwhelm whatever preparations are made, and whatever capacity survives the storm.

Amateur radio was very successful in maintaining timely contact with Kauai even under the most difficult and demanding situation of life-threatening 165 MPH winds because amateur radio operators were proactive in setting up equipment, education, training and involvement well ahead of the emergency.

Amateur radio operators equip, train, innovate and operate daily over radio frequency bands allocated to amateur radio in an effort to prepare for such an event in their own neighborhood and communities. They stand ready to serve their communities during disasters such as hurricanes, tornadoes and floods.

Involved amateur radio operators care about their community. Support amateur radio.

Copyright © 1997-2015 Ron Hashiro

Updated: August 31, 2002 DISCLAIMER: Ron Hashiro Web Site is not responsible for the content at

any of the external sites that we link to and therefore

are not necessarily endorsed by us.