|

| Radio station building on Fakaofo. |

History of Tokelau

by Peter McQuarrie, ZK3PM

Tokelau, a group of three small atolls, is isolated in the Central Pacific Ocean approximately 450 kilometres north of its nearest neighbour Samoa.

Tokelauans are part of the Polynesian family. The people of Tokelau share racial and linguistic similarities with other Polynesians, such as their neighbours in Samoa and Tonga, and the people of the neighbouring atoll groups of Tuvalu and the Northern Cook Islands, and with Wallis and Futuna.

Apparently the three Tokelau atolls were settled by three distinct groups, or perhaps differences later developed, for in ancient times the leaders of the three atolls incited war against each other. Eventually the warriors of Fakaofo brought the other two atolls under the rule of the Tui Tokelau, the king or spiritual head of Tokelau, represented by the stone god at Fakaofo.

As was the case with all small islands in the Pacific, white men came across the Tokelau Islands by accident when they were engaged in whaling or transversing the Pacific, or when purposefully seeking new discoveries or slave labour. The year 1863 brought monumental changes to Tokelau. The population was decimated by "Black Birders" who kidnapped men, women and children for slave labour in Peru. The slavers concentrated on small islands and atolls in the Pacific where the people were less alert to the danger and where there were no European missionaries to frustrate the operation or to report on the activities. They took people to work in agricultural production and in guano mining on the Peruvian coast and off shore islands. The Tokelauans were easily captured because they were concentrated in a single village on each atoll. Fakaofo and Atafu each lost 54% of their populations and Nukunonu, 26%. At Atafu only six men were left behind on the island and at Fakaofo, nine men. From 1863 onwards, the genetic mixture of the Tokelau people changed dramatically with immigration of Portuguese, German, Scottish, French, Samoan, Uvean, Tuvaluan and others to the depopulated atolls. Society was changed by the complete adoption of Christianity and the abolishment of the traditional religion and chiefly system.

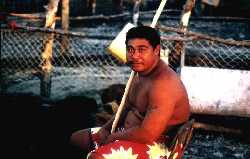

|

| Daugther of Afega Gaualofa on Fakaofo |

At the end of the First World War, the League of Nations mandated Western Samoa to New Zealand and the responsibility for Tokelau went to New Zealand as well. Western Samoa became an independent nation in 1962, and this left Tokelau isolated from New Zealand and brought to an end the free movement of Tokelauans to Samoa.

Today Tokelau is defined as a non-self-governing territory under the United Nations Charter and in 1962 it was added to a list of territories under the supervision of the United Nations Special Committee on Decolonisation. Every five years or so, representatives of the Committee visit Tokelau to ascertain that the decolonisation process is proceeding. Tokelau does not want independence from New Zealand. It has no sustainable economy of its own and depends on an annual New Zealand aid package of over $4 Million, the equivalent to $2,900 per person in Tokelau. In addition to economic reasons, Tokelauans have no wish to renounce their New Zealand citizenship and the privileges that go with it.

Environment of Tokelau

by Peter McQuarrie, ZK3PM

As with all coral atolls, those of Tokelau consist of circles of reef enclosing shallow lagoons and, around their outer perimeters, steep drop-offs into deep ocean. Upon these reefs sit small islets or motu as they are called in Polynesian. Some islets are smaller than an average sized house; others are long ribbons of land several kilometres long but seldom more than 500 metres in width and never more than four metres above sea level. In Tokelau, all ships must either drift off in the ocean or anchor on the narrow reef, in deep water but perilously close to the steep outer edge where surf is breaking, while passengers and cargo travel in small boats through the surf and over the reefs to land.

|

| Henry watching his pigs. |

The reef, which forms the base and perimeter of the coral atolls, supplies a great abundance of food resources. Amongst the corals live a great variety of fish in many sizes, shapes, colours and flavours, and there are also shellfish, octopus and turtles. The giant clam is the main edible shellfish in Tokelau and large numbers of these are taken as food. The deep ocean beyond the reef is the fishing ground of those seeking the large pelagic fish, tuna, albacore, bonito, walu and barracuda. This too is the place where the deep water snappers and other large bottom-dwelling fish are hooked, one hundred or more metres below the surface.

The coconut palm is the tree of life of the atolls for it thrives in coral sand and tolerates seawater while producing food and drink, thatch, timber, and a variety of utensils made from coconut wood and shell. The fresh sap of the coconut palm can be an important source of vitamins in an atoll environment and it is also used to make sweet syrup and is fermented for alcohol. Collecting of coconut sap, kaleve, or "toddy" as it is known in English, is undertaken by a twice daily cutting of the flower spathe and allowing the sap to drip into a container, a coconut shell or glass bottle, hung beneath.

Society of Tokelau

by Peter McQuarrie, ZK3PM

Tokelauan society is egalitarian, there is no hierarchy of chiefs and commoners. Every man and woman must work for the village, men take part in community fishing, construction projects and the unloading of cargo when ships arrive from Samoa. The women must keep the village clean and tidy and must produce cooked food for village gatherings, in addition to manufacturing mats for the church and community meeting house. Everyone is expected to take part in social events, traditional dancing and weekly cricket games. In return for work, the village sees that its people receive, each according to his or her needs. Food is shared and community labour helps families to build their houses.

|