Amateur Radio Is... |

|

...Not a Hobby! |

Amateur Radio Is... |

|

...Not a Hobby! |

I f the average Amateur Radio Operator were asked to provide a single word that best describes the Amateur Radio Service, most would probably call it a "hobby" without giving it a second thought.

As popular as this opinion may be, it's just that: an opinion, not a fact. Calling the Amateur Radio Service a hobby is a common mischaracterization that diminishes the Service's value as seen in the eyes of the public and in the professional world. It is a trivialization that makes it increasingly difficult for the Service to keep its allocated frequency spectrum protected from commercial encroachment, and makes limiting state and local restrictions on antenna structures far more challenging than they need to be.

Amateur Radio is a complex and diverse Service whose meaning cannot be reduced to that of a single word. For a true and unbiased description of what the Amateur Radio Service is, we need to look no further than the documents that officially describe the Service.

The International Amateur Radio Union (IARU) defines the Amateur Radio Service as:

A radiocommunication service (covering both terrestrial and satellite) in which a station is used for the purpose of self-training, intercommunication and technical investigations carried out by amateurs, that is, by duly authorized persons who are interested in radio technique solely with a personal aim and without any pecuniary interest.

In Canada, the Innovation, Science and Economic Development (ISED) definition is very similar:

A radiocommunication service in which radio apparatus are used for the purpose of self-training, intercommunication or technical investigation by individuals who are interested in radio technique solely with a personal aim and without pecuniary interest.

In the United States, Title 47 of the Code of Federal Regulations includes Federal Communications Commission Part 97, and expands upon the IARU definition to describe the Amateur Radio Service as having a fundamental purpose as expressed in the following principles:

Note that the word "hobby" never appears anywhere in these official definitions of the Amateur Radio Service. FCC Part 97 uses more than 23,000 words to describe the Amateur Radio Service, and not one is the word "hobby".

While individuals may engage in Amateur Radio for personal enjoyment, this does not equate the Service as being a hobby. A paperweight can be used to drive a nail into a piece of lumber, but that doesn't make a paperweight a hammer. Collecting, organizing, and displaying QSL cards is clearly a hobby, radio contests are clearly sports activities, and speaking with friends (or seeking new ones) is clearly an act of socialization, but these specific pursuits don't define the overall Amateur Radio Service as a hobby, sport, or social activity any more than the baseball field on the campus of Princeton University would define the Ivy-League institution as a playground.

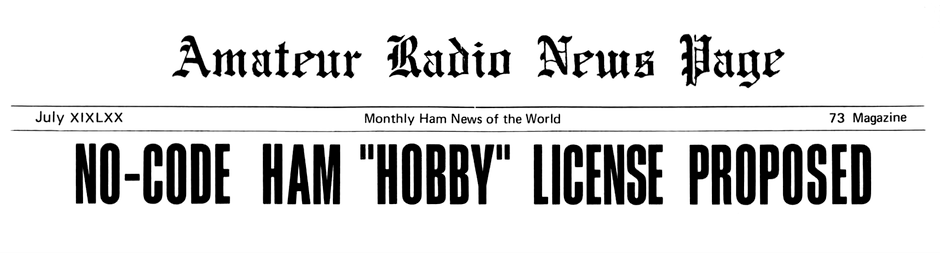

There have been numerous efforts to create "Hobby" or "Communicator" style licenses in the United States to cater to individuals interested in radio communications strictly as a hobby. None of the proposals made ever earned any support from the FCC.

One such effort, RM-1633, proposed by Wayne Green, W2NSD (SK) on May 25, 1970 envisioned a "Hobby Class" Amateur Radio operators license to provide FM-only privileges between 220.5 and 224.5 MHz. A licensing exam covering knowledge of FCC Rules and Regulations, but without having to demonstrate mastery of radio theory or Morse code proficiency, would be proctored by a holder of a General Class Amateur Radio Operator's License.

Although the Hobby Class License proposal made by Wayne Green failed, it clearly defined some of the fundamental differences between what was expected of an Amateur Radio Operator versus what was expected of a lesser "Radio as a Hobby" Operator.

A petition made a year later by the "United CB'ers of America" (RM-1841) sought to employ the 27 MHz Citizen's Radio Service band for "hobby" use only, while transferring all emergency and call channel operations from 27 MHz to 220 MHz.

These are merely two examples, but given the long history of individuals and organizations who have proposed various "radio as a hobby" licenses and services over the years, if Amateur Radio were truly a "hobby", then there would never have been any interest in proposing these hobby licenses and services in the first place.

The word "Service" has several different meanings that apply to Amateur Radio in various ways. and this is often the source of confusion and debate. While Amateurs are under no obligation to perform duties for the direct benefit of the general public, the FCC and other organizations often credit Amateurs for the communication services they voluntarily provide during emergencies. Having a wide range of frequency agility, access to repeaters and satellites (that were designed and built by Amateurs in the first place), proven technical knowledge and practical understanding of antennas, transmission lines, propagation, and transceivers, combined with the ability to build, repair, and/or modify communications equipment and to create ad hoc networks on our own without the need for any FCC certifications puts Amateurs ahead of commercial communication networks specifically designed to serve first responders when "all else fails".

Perhaps more importantly, the word "Service" also refers to "the administrative division of a government" that provides the rules, licensing, enforcement, and resources necessary to allow the Basis and Purpose of the Service to exist and flourish in the first place. Of the many Radio Services defined by the FCC, only a small fraction directly benefit the general public. The vast majority relate to support functions the FCC provides to its licensees. As such, it can be said that Amateur Radio is neither a hobby nor a service, and those who refer to it as a "Hobby/Service" are doubly mistaken in their attempt in trying to be noncommittal.

The Amateur Radio Service is an Amateur Activity, just as there are Amateur Astronomers, Amateur Historians, Amateur Geologists, Amateur Photographers, Amateur Storm Chasers, and Citizen Scientists. By definition, Amateurs and Professionals are functionally linked and even collaborate with one another from time to time. Hobbyists seldom, if ever, collaborate with professionals in any meaningful way.

Hobbies focus on personal satisfaction with minimal obligation or regulation. Amateur activities involve serious, skilled, and sometimes socially impactful participation, often with a structured or regulated framework, even if the participants are unpaid. Amateur activities often require some degree of co-dependence on other practitioners or professionals, whereas hobbyists work in solitude.

| Purpose | Primarily for personal enjoyment, relaxation, or entertainment | Can involve enjoyment but often includes public service, technical development, or professional-level skill |

| Skill Level | Skill is optional and often casual | Often requires training, certifications, or skill development (e.g., licenses in Amateur Radio) |

| Public Benefit | Rarely benefits others directly | May provide community service, technical support, or educational outreach |

| Regulation | Typically unregulated | Frequently regulated (e.g., FCC regulations for Amateur Radio, sports organizations for amateur athletics) |

| Monetary Compensation | No compensation; strictly recreational | No pay, but contributions may rival those of professionals (amateurs often volunteer) |

| Recognition | Generally informal or personal | May involve formal recognition, awards, or licensing |

| Examples | Knitting, stamp collecting, video gaming | Amateur radio, amateur astronomy, amateur sports, citizen science projects |

| Professional Counterparts | None | Commercial Radio Operator, Astronomer, Professional Athlete, Scientist |

Hobbies are independent pursuits that benefit the individual practitioner only. A person touching a paint brush to canvas for the first time today can neither stand on the shoulders of those who painted before, nor build in any way on their previous efforts. It's a strickly personal effort. Hobbies are absorbing, but they do not transform the individual. They fill the mind without altering it, and they provide a healthy counterbalance to work.

In contrast, amateur activities often shadow the work done in a commercial or professional field to a degree that is limited only by the resources available and the enthusiasm of the practitioner. Amateur activities transform the individual and build upon earlier successes as well as the accomplishments of others. Amateur activities require a more professionally defined and developed skill set than hobbies, and can produce outcomes that may directly or indirectly benefit society as a whole. In addition, amateur activities can produce outcomes that complement, rival, or even surpass those of their professional counterparts, while providing something more personally gratifying to the practitioner than mere material compensation.

While Professionals have the power to change the world, Amateurs can, and occasionally do, as well. Recall that Albert Einstein was an amateur scientist who was employed as a patent clerk when he made his most ground breaking contributions to the field of physics. Michael Faraday was a humble bookbinder with no formal education in science. However, his work in electromagnetism and electrochemistry led to foundational discoveries that formed the basis of modern electrical engineering and physics. Charles Darwin was independently wealthy when he developed his theory of evolution. Gregor Mendel, one of founders of genetics, was a monk during the time of his scientific breakthroughs. Benjamin Franklin, one of the founding fathers of the United States, was also a self-taught scientist whose contributions to the understanding of electricity changed the course of history. Much like these and other Amateur Scientists, Amateur Radio Operators have a long, proven history of contributing to society and the professional world as well.

Another fundamental difference between hobbies and amateur activities is that amateur activities typically have professional counterparts and share some overlap in knowledge and skills used in the professional world. Hobbies share no such connection.

The most obvious professional counterpart to the Amateur Radio Service would be any commercial, military, marine, aviation or industry service requiring a commercial radio operator's license or other professional certification in order to build, certify, or operate a radio transmitter within legal guidelines. However, the myriad of activities with which Radio Amateur's engage and specialize effectively multiplies the number of skills that overlap between Amateur Radio and the professional world many times over.

As such, the professional counterparts to Amateur Radio are widespread and span multiple fields, including communications, emergency services, space communications, broadcasting, and wireless network engineering. The skills learned and experiences gained in Amateur Radio, such as technical problem-solving, equipment management, and communication protocols, are directly applicable to many of these industries, which is one reason why many Amateur Radio Operators often go on to pursue professional careers in related fields.

| General radio communication | Commercial Radio/TV Broadcasting | RF transmission, signal modulation, antenna design |

| Emergency Communications | Emergency Services, Disaster Response | Incident coordination, mobile comms, public safety radio operation |

| Satellite (e.g. OSCAR) communications | Commercial and Military Satellite Communications, Aerospace Engineering | Satellite tracking, uplink/downlink protocols, orbital mechanics, telemetry, link budgets, Doppler shift |

| Microwave and high-frequency (HF) communications | Telecommunications (Microwave, Cellular, Wireless ISP) | Frequency allocation, line-of-sight links, repeater use |

| Antenna building, design, optimization, RF experimentation | RF Engineering | Impedance matching, transmission lines, signal propagation, analog/digital transmission and reception, electromagnetic compatibility, network analyzers, spectrum analyzers, antenna modeling software |

| Equipment repair, modification, alignment, kit building | Electronics Technician | Electronics lab equipment skills, soldering, troubleshooting, repair, calibration, and testing |

| "Homebrewing" (designing/building) radio equipment | Electronics Engineering | Ideation, circuit design, construction, testing, troubleshooting, performance evaluation |

| Tactical and mobile setups (e.g. POTA, Field Day ops) | Military Communications | Field radio ops, equipment ruggedization, off-grid power generation, management, and use |

| Skywarn and weather net participation | Meteorology, Environmental Monitoring | Observational reporting, real-time data communication, storm spotting |

| Packet radio, FT8, APRS, ALE/PACTOR, Winlink | Computer Networking, Digital Communications | Data encoding, error correction, digital modes, low-bandwidth networking |

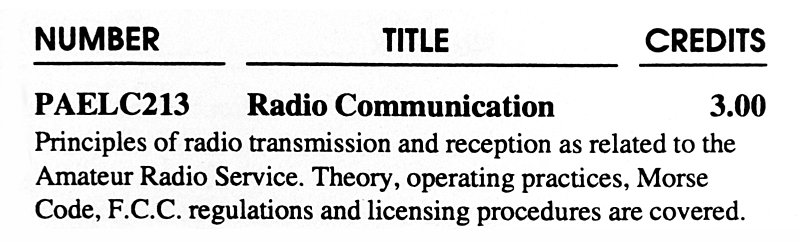

Much like Amateur Scientists, the technical skills developed within the Amateur Radio Service can parallel those required for success in the professional telecommunications field. Evidence of that equivalence can be found in the world of higher education. Thomas Edison State University, a fully accredited university in Trenton, New Jersey, awards credit by way of portfolio assessment for college-level learning that can be acquired through professional, military, and other well-documented life experiences. Among the courses available for college credit (at least in the 1990s) was a Sophomore-level 3-credit course entitled, "Radio Communication", PAELC213:

To earn credit, an applicant had to demonstrate a valid license in addition to evidence as to how the material needed to pass the licensing exam was learned. (Simply studying the question pool Q&A is insufficient evidence to qualify for credit.)

Additional courses that provide students a working knowledge of electronic communication systems, AM, FM, single-sideband, video, digital modulation schemes, demodulation methods, receivers, transmitters, oscillators, RF voltage and power amplifiers, test equipment, and laboratory measurements were also available. These are concepts that can be readily acquired through real-world amateur radio operating experiences and experimentation — a claim that cannot be made for woodworking, embroidery, or any other hobby. Furthermore, some of the questions on the Amateur Extra Class licensing exam relating to electronic theory are similar, if not identical, to those that appear on the commercial FCC General Radio Operator's License exam.

More evidence of the value of Amateur Radio adds to higher education can be found at Carnegie Mellon University in Pennsylvania, where a course in Amateur Radio was recently added to its curriculum for engineering students. In addition, Honors students in chemistry are being given the opportunity to add Amateur Radio to their first-semester course load at a college in West Bengal, India.

Further evidence of Amateur Radio's value in the professional world can be found at the West Point U.S. Military Academy where an Amateur Radio Club is dedicated to providing cadets with the opportunity to learn about a diverse array of communication capabilities including the Internet, cellular radio, packet radio, slow scan television, satellite, line of sight communications, repeaters, and over the horizon communication techniques. The cadets gain a fundamental understanding of current technology that is useful in our increasingly technologically dependent Army. The club also reinforces lessons learned in their engineering classes and enables the cadets to contact other radio operators internationally to practice their foreign language skills.

As of September 2022, the U.S. Navy-Marine Corps was actively seeking Amateur Radio Operators and re-establishing the Navy's Military Auxiliary Radio Service (MARS).

In 2023, the National Radio Astronomy Observatory was seeking individuals interested in participating in an online Amateur Radio project entitled, "Exploring the Electromagnetic Spectrum", where participants could earn Amateur Radio licenses while gaining hands-on experience learning about the electromagnetic spectrum and it's use in STEM fields.

Also in 2023, NASA issued a request seeking the assistance of Amateur Radio Operators in collecting scientific data during the upcoming solar eclipses so that the greater scientific community might gain a better understanding of the behavior of the Earth's ionosphere.

The Radio Club of America and the National Association of Broadcasters are among some of the well-respected professional organizations who proudly support Amateur Radio.

During his March 15, 2009 LIMARC Technical Net, Dick Knadle, K2RIW (SK), estimated that 90% of the day-to-day working knowledge he used for his work as an Antenna Engineer and later as an Engineering Consultant came from his experiences in Amateur Radio, while only 10% came from his formal college-level education.

Listen to Dick explain this in his own words:

The value of Amateur Radio is reflected in the accomplishments the Service makes that benefit society, and the support it receives from both society and the professional world in return. Throughout history, Amateur Radio Operators have developed new communication technologies, founded new industries, built economies, empowered nations, and saved lives in times of emergency.

Here are just a few examples that illustrate where, unlike hobbies, Amateur Radio activities and experiences have yielded positive benefits to society as a whole.

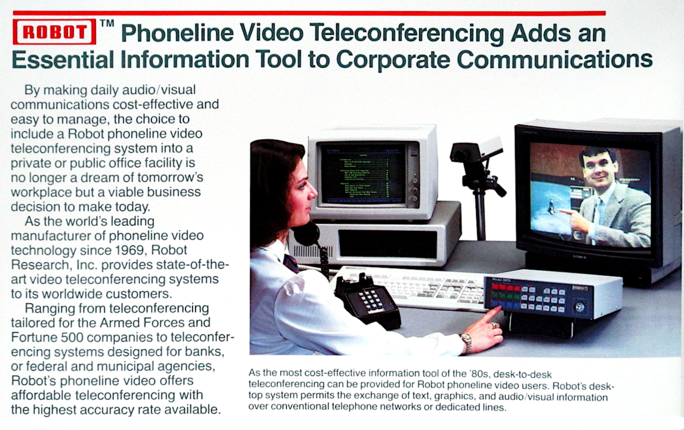

Copthorn MacDonald, W0ORX, invented Slow-Scan Television (SSTV) in the 1950s for use by Amateur Radio Operators. By the late 1970s, Clarence Munsey, K6IV, of Robot Research, Inc. wrote a patent for a video scan converter that not only saw use by amateurs in the form of the Robot Model 400 scan converter, but also employed the same technology in later products manufactured by the same company for commercial security video and early telemedicine applications. Slow-Scan Television has also been used outside of Amateur Radio in the surveillance of active volcanoes and in the delivery of engineering continuing education in remote areas.

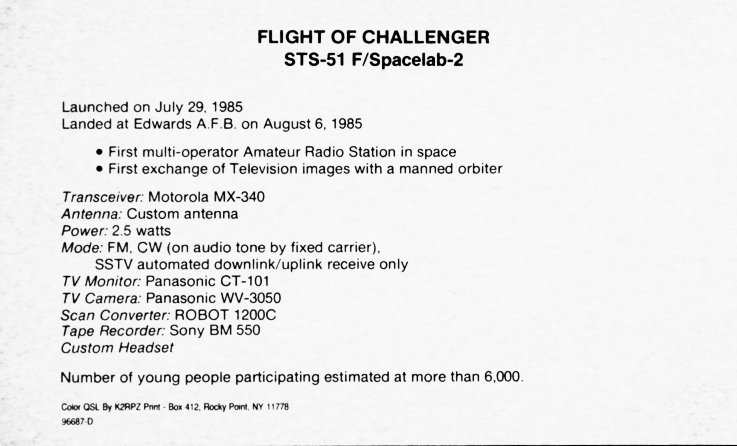

The Shuttle Amateur Radio Experiment (SAREX) carried onboard Space Shuttle Challenger by NASA Astronaut Tony England, W0̸ORE in 1985 carried with it SSTV hardware, and its use established the very first time a 2-way exchange of television images was made between the earth and a manned orbiter. NASA was so impressed by this historic accomplishment that it adopted the practice in their space program from that point forward.

|

|

The first direct satellite communications between the United States and the U.S.S.R. took place on December 22, 1965 by Radio Amateurs utilizing an Amateur Radio communications satellite known as OSCAR-4.

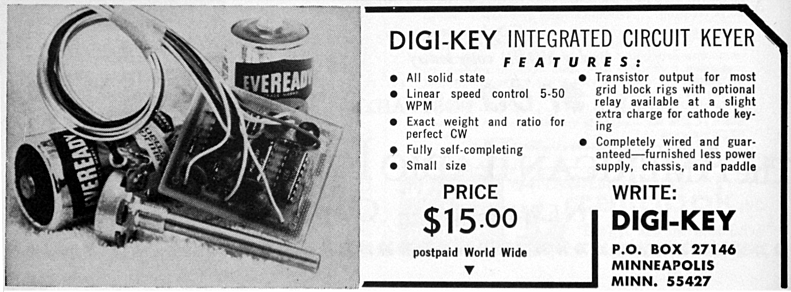

In 1969, Ron Stordahl, N5IN (now AE5E), developed a Morse Code Keyer in both kit and assembled form. Ron's "Digi-Key Integrated Circuit Keyer" was the seed that grew into today's $4 billion Digi-Key Electronics Corporation. Remaining loyal to its roots, Digi-Key's support of Amateur Radio continues to this day through (among other things) its sponsorship of the Ham Radio Workbench Podcast.

Dr. Karl Meinzer, DJ4ZC, invented Interpreter for Process Structures, a threaded programming language developed for the AMSAT Phase III Amateur Radio satellite. IPS was the first use of a high-level programming language onboard a spacecraft. DJ4ZC also invented the concept of High Efficiency Linear Amplification by Parametric Synthesis (HELAPS).

The Radio Amateur Satellite Corporation pioneered the development and successful application of low-cost Microsat and Cubesat satellites that today are widely used both inside and outside the world of Amateur Radio.

Similarly, a group of researchers at the University of Surrey led by Dr. Martin Sweeting, G3YJO, produced the UoSAT-1/OSCAR-9 Amateur Radio satellite using low-cost, off-the-shelf components. Their second satellite, UoSAT-OSCAR-11, was built and launched in just 6 months time. This success led to the creation of Surrey Satellite Technology LTD in 1985 and the development and launch of more than 70 satellites.

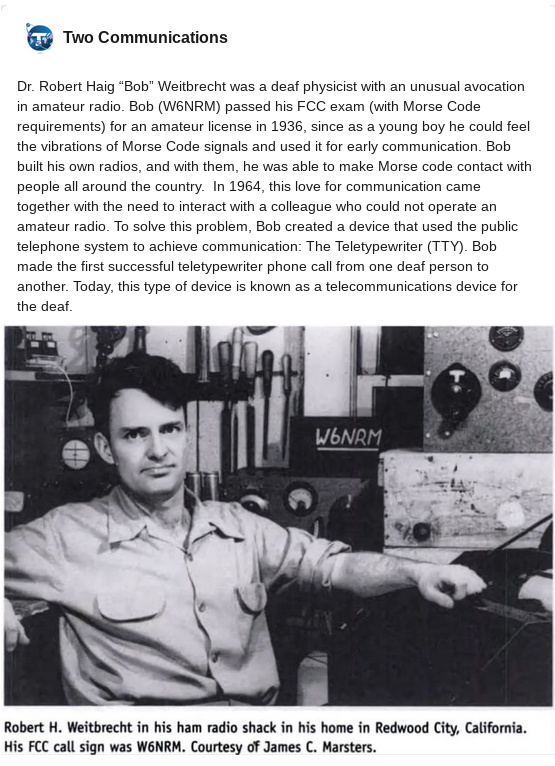

Dr. Robert Haig "Bob" Weitbrecht, W6NRM (SK), a hearing impaired Amateur, applied his knowledge and experience of Radio Teletype (RTTY) toward his invention of the TTY (Telephone Teletype) in the 1960s that permitted hearing impaired individuals to communicate over a telephone. During the process, Bob also invented the Acoustic Coupler that saw widespread application in modems used by early PC users decades later.

In May 1993, U.S. House Joint Resolution 199 formally recognized the achievements of Radio Amateurs, and established support for Amateurs as a national policy. Its corresponding Senate Joint Resolution 90 was signed by President Clinton, and became Public Law 103-408 on October 22, 1994.

In 2005, John Kanzius, K3TUP (SK) teamed up with cancer researchers at M. D. Anderson and Rice University to develop a cancer treatment that involves impregnating cancer cells with metallic nanoparticles and heating them with RF energy at 13.56 MHz to kill the cancer while sparing the surrounding healthy tissue. John stated that if it were not for his Amateur Radio background, "and all the days of experimentation to improve my station, this new procedure for treating cancer, which continues to show such promising results, would probably not be on the cutting edge at the largest cancer center in the world [M. D. Anderson]." (Source: link)

Dr. John Kraus, W8JK, was the inventor of the Helical Antenna, the Corner Reflector Antenna, and other designs widely used in the telecommunications world.

The Citizen Weather Observer Program was started by Amateur Radio Operators employing Packet Radio communications technology, but has since grown to allow any interested individuals with Internet connections to participate. Similarly, the National Weather Service's Skywarn Storm Spotter Program has relied on Amateur Radio Operators for delivering real-time weather observations to the National Weather Service during serious weather events for decades.

An impressive amount of ionospheric research is being undertaken by members of the HamSCI Ham Radio Science Citizen Investigation group. HamSCI recognizes that Amateur Radio operators have made significant contributions to radio technology and the understanding of radio science, and that recent advances in the fields of computing, software defined radio, and signal processing provide unprecedented opportunities to continue and extend one of Amateur Radio's primary purposes: To contribute to the advancement of the radio art. HamSCI is officially recognized as a NASA Citizen Science Project.

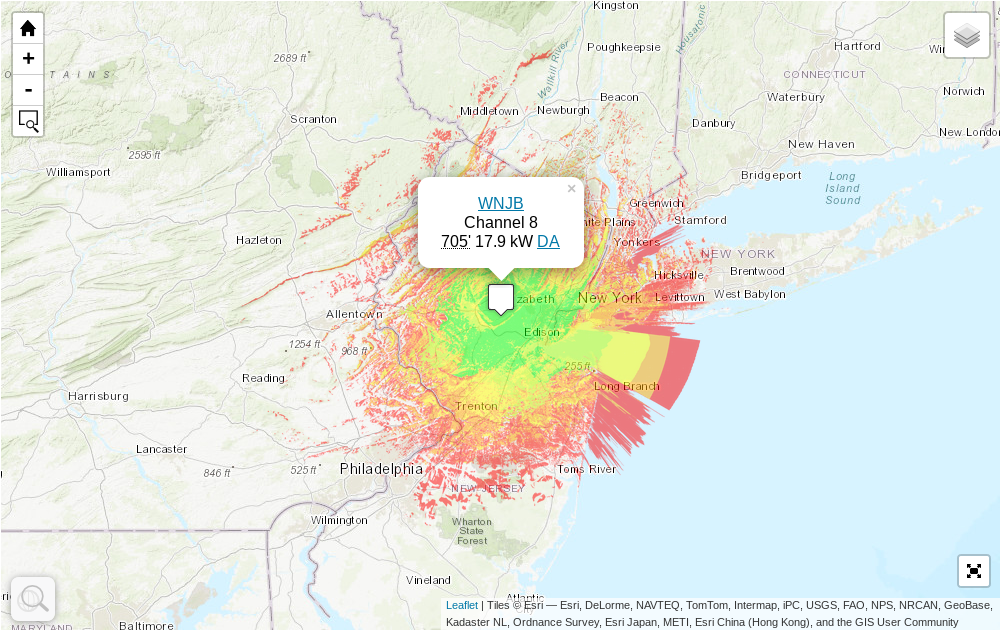

As an Amateur Radio Operator, I have personally developed two pieces of software that have made positive impacts both within and beyond the world of Amateur Radio. My satellite tracking software, PREDICT was created so I could communicate through OSCAR satellites and predict in advance the time of their arrival. My SPLAT! software was created to visualize the operational range of an Amateur Television (ATV) repeater system I designed. Both projects have since been adopted for use in the professional world, and have become successful far beyond what I could have ever imagined.

Each of my software applications were released to the public, free of charge, under an Open Source Software License where they grew over time and found homes at professional institutions such as NASA, the European Space Agency, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Stanford University, Cornell University, CalTech, Stanford University's Space Systems Development Laboratory, the U.S. Naval Academy, Space Data Corporation, ArgonST (a subsidiary of The Boeing Company), and New Mexico Search and Rescue, to name just a few.

Amateur Radio is a dynamic training platform that goes far beyond emergency communications. It offers hands-on learning in areas such as electronics, physics, digital communications, and even software development. Calling Amateur Radio a "hobby" seriously limits its potential to inspire the next generation of engineers, scientists, and tech professionals. It also undermines Amateur Radio's legal and regulatory standing, making it easier for policymakers to devalue the Service and reassign spectrum allocated to its use and restrict its future capabilities.

This concern dates back many decades. In May 1965, William S. Grenfell, W4GF, of the Federal Communications Commission cautioned that the justification for the continued allocation to the Amateur Radio Service of a substantial portion of the radio frequency spectrum by the FCC in the face of important demands by other radio services could not be founded on anything other than a continued movement of the Amateur Service toward the goals specified in Section 97.1 of the Amateur Rules.

Translation: Calling it a hobby and treating it as such will neither sustain nor protect the Service from commercial interests who can justify a greater public benefit for use of the radio spectrum currently allocated to Amateur use.

More recently in 2023, the Amateur Radio Service found itself opposing a proposal made by the "Shortwave Modernization Coalition" (SMC), who sought changes be made to FCC Part 90 to permit the placement of 20,000-watt radio transmitters immediately adjacent to seven HF Amateur bands for the purpose of making long-distance, high-speed stock trades.

In its detailed response, the National Association for Amateur Radio (a.k.a. the ARRL) justified its argument against the SMC proposal by stating that the RF spectrum that could be subject to harmful interference from the SMC proposal was used by Amateurs for purposes that included "vital support during disaster recovery and mitigation, technical and scientific experiments, and propagation studies".

Nowhere in the ARRL's defense and protection of the Amateur Radio Service was the Service referred to as being a "hobby" for reasons that by now should be abundantly obvious.

Furthermore, labeling Amateur Radio as just a "hobby" also reinforces the stereotype that it's merely a pastime for older men wishing to live in the past, rather than a legitimate and effective pathway into today's STEM fields. This common misconception diminishes Amateur Radio's appeal to students and young professionals pursuing career-building opportunities who could be the "new blood" needed to sustain and grow the Service in the decades to come.

Last but not least, calling it a "hobby" excuses a lot of poor behavior that has no place in Amateur Radio.

The Amateur Radio Service is a structured and purposeful communication service with roles that extend far beyond personal enjoyment. Its legal definitions, societal contributions, and organizational missions collectively affirm that it serves as a vital component of public communication infrastructure and a valid career pathway that ties directly into the flourishing fields of electronics, communication systems, satellite technology, and networking. Calling it a "hobby" not only demonstrates a fundamental misunderstanding of the basis and purpose of the Service, but it also poses real dangers to its perception, effectiveness, and long-term sustainability.

The words we use to describe ourselves matter. Correcting this mischaracterization will require a culture shift both inside and outside the Amateur Radio Community, from how operators talk about what they do, to how they present themselves in the public eye and express themselves on social media, in published materials, over-the-air, and through on-line discussion forums.

It won't be easy, but history has shown that perpetuating the widely believed and too-often parroted (without thinking) falsehood that the Amateur Radio Service is a "hobby" has never led to anything productive and could very well lead to our undoing. So, why continue doing it?

If the IARU, FCC, and ISED don't define the Amateur Radio Service as a "hobby", then we shouldn't either.

73 de John, KD2BD

|

|

John

Magliacane |