|

Let's get basic for a few paragraphs... and if you're an old-timer, you might want to read through this section just to see if we got it right. First, what exactly is a "repeater"? And why do we use them? Without repeaters, the communication range between Amateur VHF-FM mobile and handheld radios at ground level is limited -- five to fifteen miles for mobiles, and just a couple of miles for handhelds. The distance you can communicate is usually referred to as "line-of-sight" -- you can talk about as far as you can see (if you cut down the trees). To extend our range, we use repeaters. A repeater is a specially designed receiver/transmitter combination. When you operate through a repeater, its receiver picks up your signal on the input frequency, and the transmitter re-transmits -- or "repeats" -- you on the output frequency. For example, the KB9OHY repeater hears you as you transmit on 147.645 MHz, and repeats you onto 147.045 MHz. Repeater antennas are located on tall towers, buildings, or mountains, giving them much greater range than radios with antennas near the ground. And when you're in range of a repeater, you can talk to everyone else in range of that repeater. The O.C.A.R.C. repeater is located in Paoli IN, on a hill just south of town (see map below). Its antenna is on the top of a tower that puts it well above the average terrain. A mobile station running 50 watts can reliably communicate through the repeater out to about 25/35 miles. So if you were 25/35 miles north of the repeater, you could talk to someone 25/35 miles south of the repeater. That's 50/70 miles between you -- a whole lot better than the 10 or so miles you could cover without the repeater!

Map of Paoli Indiana Lat: 38° 32' 11" N Lon: 86° 28' 2" W Grid Square EM68sn There are literally thousands of repeaters across the US (and the world). Each one can have it's own peculiarities and unique operating procedures, but there are some basics that apply to almost all of them. Really complete instructions would fill a book, bore you to tears, and start some fights about what's correct and what's not (operating procedure is a matter of strong opinion in Ham Radio!). We'll risk all of that now, but try not to fill a book. PLAIN OLD TALKING. Mostly, you're here to get on the air and chat, right? OK, first you set your radio for the repeater you want to use. Don't know how to find a local repeater frequency? The KB9TMP web site has a list of the local area 2-meter & 440 repeaters. Check it out here. If you're outside the Orange County area, you'll need a repeater directory. They're available from the ARRL and the Artsci Publications. At the very least, you can just scan across the band for activity using this chart as your guide (click on the chart for a larger view): Once you've selected a repeater and dialed it up on your radio, the first thing you should do is... LISTEN for a minute. Repeaters are party lines. Lots of people use them on and off throughout the day, and the one you've selected may be busy with another conversation right now. So listen for a minute. (Does anyone remember what "party lines" are? Kids, ask your grandparents!) If the repeater isn't busy, key your transmitter and say something like "KB9OHY listening. Anybody on the frequency?" (Use your own call, not the club's). You could call CQ, but that time-honored method of seeking a contact never caught on with FM operators. Somebody may even tell you your not "supposed" to call CQ on FM, but you can. When you release your transmit button, most repeaters will stay on the air for a few seconds, and many will send some kind of "beep." Then, the repeater transmitter drops off the air. The beep is there to remind everyone to leave a pause between transmissions in case someone wants to break in. Even if there's no beep, leave a pause. Somebody may have just come across a traffic accident and needs the repeater to report it. If nobody leaves a pause between transmissions, they can't break in. If somebody answers you, then have a good time! You can talk about anything you want -- there are not many rules about the content of Amateur conversation. You can't use Ham Radio to conduct your business, but you can talk about where you work and what you do. Prime time TV language has been peppered with some "hells" and "damns," and so has language on some repeaters. The O.C.A.R.C. discourages that. You're not having a private conversation -- you may have lots of listeners, some of them children. Keep that in mind as you choose language and subject matter. How long do you talk? I see you're catching on to the party-line concept. Maybe somebody else wants to use the repeater when you're done. There's no hard rule. It depends on the time of day (rush hours are prime time for mobiles, evening is also a busy time, while 2 a.m. is pretty empty), and who else might want to use the repeater. If you've been interrupted several times by others needing the repeater to call someone, maybe you've been on a bit too long. THREE-WAY RADIO. Not all conversations are strictly two-way. Three, four or five or more Hams can be part of a "roundtable" conversation (five or more will be pretty unwieldy). A free-wheeling roundtable is a lot of fun... and it poses a problem: when the person transmitting now is done, who transmits next? Too often, the answer is everybody transmits next, and the result is a mess. The solution is simple -- when you finish your transmission in the roundtable, specify who is to transmit next. "... Over to you, NAME &/or CALLSIGN. WE PAUSE FOR STATION IDENTIFICATION.The Rules say you must ID once every 10 minutes. The O.C.A.R.C. is big on clear identification when you use our repeater, but you don't have to overdo it. Give your callsign when you first get on (this isn't specifically required by the rules, but the O.C.A.R.C. encourages it on our repeater), then once every 10 minutes, and again when you sign off. You don't have to give anyone else's callsign at any time, although sometimes its a nice acknowledgment of the person you're talking to, like a handshake. BREAKING IN. Repeaters are shared resources -- the party-line. There are many times and reasons that a conversation in progress might be interrupted. You might break in to join the group and add your comments on the subject at hand. Someone might break in on you to reach someone else who is listening to the repeater. You might have to report an emergency. How to break in is the subject of debate and disagreement. Here are some suggestions:

Cool down. It doesn't happen often, but it does happen -- it's a big world out there, and there are some bad people in it. Some of them find a Ham Radio now and then, and discover the delight of offending an audience. The key word is audience. Deliberate interference and bad language are designed to make you react. The person doing it wants to hearyou get mad. They love it. And if they don't get it, they go away, usually quickly. So when you hear the rare nasty stuff on the repeater, our advice is to please ignore it completely. Don't mention it at all on the air. Sometimes a repeater control operator will decide that the best way to handle the situation is to turn off the repeater or one of its functions for a while, but the rest of us should bite our tongues and be silent. AUTOPATCH. The O.C.A.R.C. does not have autopatch ability, due to the fact that Verizon requires us to have a "business" phone line. With us being such a small club our operating budget can't cover the cost of business phone service. We are however looking into options that would be more in line with our budget, so some day we may have autopatch service again. Business. The FCC says you can not use Amateur Radio for your business or employment. Which means no conducting business over the air, but you can use Amateur Radio to sell a "used" item that is of interest to other amateur radio operators. Many clubs have a swap net or swap related portion of a regular net just for that purpose. You just can't do it if your "business" is selling ham radio gear. Computers, scanners, radios, and antennas are all ok, but knives, guns, cars, and other "NON" ham related products are forbidden. DX! Well, you probably won't be hearing Carjackistan on two-meters anytime soon, but VHF does have it's own form of DX. A few paragraphs ago we mentioned that the KB9OHY repeater had about a 25/35 mile range. Usually. Sometimes, though, VHF/UHF "opens up," and stations can be heard for hundreds of miles. This is another book-length subject. We'll just squeeze in that VHF/UHF band openings are a double-edged sword. It's exciting to talk to someone 200 miles away, and it's OK, too. But keep in mind that repeaters were designed to cover local territory, not half the country. So when the band opens up, there is the potential for lots of interference as well as lots of fun. Repeaters on the same frequency will suddenly be too close together. You could very easily be keying up two or more of them at once. To be responsible, get to know where your signal is going (a repeater directory will help). Use a directional antenna, minimum power and keep your conversation short. On the KB9OHY repeater, we have to be particularly sensitive to the other 147.045 repeaters. When the band opens, their users begin keying up our repeater, and we begin keying up their repeaters. While normally not fatal, this can be irritating. Running minimum power, either mobile or from home, will help. How much power is too much? Within 10 miles of the KB9OHY repeater, five to ten watts into a mobile antenna is all you need. 45 watts is excessive. At home, with an antenna up on the roof, 45 watts is really excessive for talking through a local repeater. When the band is open, even a five-watt mobile signal can travel several miles. At those times, patience and courtesy will help a lot. SIMPLEX. This may come as a shock, but you don't have to use a repeater to communicate on two-meter FM. You can use simplex, which means yourradio talking to my radio directly. We do have that five to fifteen mile range -- much more if we're on our home stations. Why not use it? But don't just pick any old frequency your radio can generate to talk simplex! You may end up on the input of a repeater and interfere with people you can't hear. Use the Band Plan simplex channels:

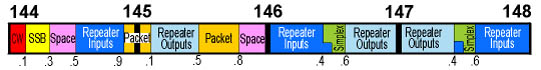

BAND PLAN? Yes, there is a plan organizing frequency use for two-meters (and, for that matter, every Amateur band). For the most part, band plans are voluntary -- the FCC regulates only a few modes and band segments. Band plans for HF are international, and you'll find them on the ARRL web site.

Here's a simple block diagram based on the ARRL's Two Meter Bandplan.

The complete two-meter band plan is much more detailed than this chart shows. For a really complete look at all the band plans, The ARRL Band Plans, page showing every operating band and it's band plan, with a link to the "Considerate Operator's Frequency Guide" page. (And if you bought a dual-band radio, the chart also shows the UHF band plan.) The two-meter band plan looks complex, perhaps even convoluted, doesn't it? That's because two-meters grew in spurts, a little here, a little there. In the early 1960's, there was just a little AM and SSB activity centered just above 145.0 MHz. FM and repeaters were barely getting started, around 146.94 MHz. The rest of the band was empty. FM began to grow, but it was constrained by FCC regulations that let Techs use only 145.0 to 147.0MHz. Satellites were launched, packet was invented, and rules changes moved Techs and repeaters around the band. Everyone needed a slice of the pie, and the result is the band plan you see in the chart. Check out the frequency coverage of your shiny new two-meter FM handheld. It covers the whole band, doesn't it? But if you use it any-old-where, you might interfere with someone - maybe an SSB operator, or a satellite station, or a repeater input. Please stick to the Band Plan channels. If we all do that, we'll get maximum use and enjoyment out of the band. EMERGENCIES. Helping to communicate in emergencies is Amateur Radio's #1 reason for existence. Repeaters, are excellent tools for emergency communication, and the most frequent type of emergency called in is the traffic accident. And that's why we leave a pause between transmissions -- you never know when someone (you) will need the repeater in an emergency.

During these operations, the active repeater will probably be "closed" to regular conversations. But unless a major disaster has hit the area, there will be other repeaters available for regular activity. Ask the net control station for the status of the repeater. PUBLIC SERVICE. Hams across the country regularly help charitable organizations with communications during fund-raising events like bike-a-thons. Repeaters and simplex are both used for public service events. Their activity isn't too compatible with other hams "rag-chewing" on the same channel, so during the event a repeater will again be very busy. If you need to make a call please wait for a break and keep it short so everyone has a chance to use the repeater. GIVING DIRECTIONS.What's "giving directions" doing in a repeater operating guide? Just listen for a while, and you'll hear why. We give a lot of directions on repeaters, to locals in an unfamiliar part of town, and to traveling hams visiting the area. And, sad to say, too often we do it badly. One person will give adequate directions, and someone else just has to break in to give his favorite shortcut. Or somebody gives a two-minute long string of street names and landmarks, non-stop. The poor, lost ham who asked will then thank everyone politely, turn off the radio, and pull into a gas station to try again. We literally fall all over each other trying to be too helpful! If someone has given directions that will get the traveler to her destination, let it be. Make a correction only if the directions are dead wrong (they'll end up in Carjackistan?). If it's your turn to give the directions, keep them short and simple. And it might be helpful to find out where the mobile station is before telling him where to go! Also "NEVER" give directions like "take the old Wendell farm road and make a left by the old Johnson place, keep going till you reach Copland hill and turn right at the house that Grandma Purdy had", if the ham asking directions don't know the area they sure will "NOT" know where the Wendell farm, the old Johnson place and Grandma Purdy's was. NETS. Repeaters are great places for nets, and there are lots of nets. A net is an organized on-the-air activity. We've mentioned a few already, like SKYWARN and RACES, but there can be many other types -- traffic nets, rag-chew nets, specialty topic nets, club information nets, and more. When a net is active on a repeater, the repeater is "closed" to other activity. The net-control is in charge of the frequency, and all communication should be directed to that station first. The O.C.A.R.C. holds our net on Monday nights at 8 PM local time or 01:00 UTC. It is an open net and all licensed hams are invited to participate. TIMERS.Almost all repeaters have something called "timers." A timer is a clock that starts counting when you begin to transmit through the repeater. Typically, this clock is set to "time-out" after about three minutes. That means that if you transmit continuously through the repeater for more than three minutes, the repeater will go off the air (we call it "timing out"). Repeater timers usually reset to zero when you, the user, stop transmitting. If the repeater has a "beep," the timer probably resets when you hear the beep. So you have to keep your transmissions under three minutes, and always wait for the beep, to avoid having your transmission dumped by the repeater timer. The three-minute timers are one way to comply with the FCC rules for stations being operated by remote control (most repeaters are remotely controlled). They are not designed as punitive measures for gabby hams... but come to think of it, given the party-line nature of repeaters, and the potential for that emergency traffic, it's a good idea to keep your brilliant monologues a bit shorter anyway. If you must ramble on, orator that you are, don't forget to let the timer reset, and check if somebody else needs the repeater, after a minute or two. CODED SQUELCH. There are three kinds of Coded Squelch commonly available to Amateurs: CTCSS, commonly called "PL" (Private-Line, a Motorola trade name), and also called "Subaudible Tone", DTMF, more generally known as Touch-Tone (an AT&T trade name), and DCS, Digital Coded Squelch also known by the Motorola brand name Digital Private Line "DPL". The purpose of coded squelch is to allow special signaling from a transmitter to a receiver, either to turn the receiver on, or to access special functions (like autopatch). CTCSS (Continuous Tone Coded Squelch System) keeps your receiver quiet on a busy channel until the station you want calls. It adds a "subaudible" tone to your audio, one of 37 very specific frequencies between 67 and 250.3 Hz. Yes, humans can hear these frequencies quite well, so they're "subaudible" because your receiver's audio circuit is supposed to filter them out. A receiver with CTCSS will remain silent to all traffic on a channel unless the transmitting station is sending the correct tone. Then the receiver sends the transmitted audio to it's speaker. In commercial radio service, this allows Jane's Taxi Company and Bob's Towing Service to use the same channel without having to listen to each other's traffic. In Amateur Radio, some repeaters require users to send the correct CTCSS tone to use the repeater. This may mean the repeater is "closed," for use only by members, or it may simply be used to avoid being keyed up by users of another repeater on the same frequency. You can use CTCSS yourself, if you have a decoder in your radio, to silently monitor a busy channel for stations calling just you. Arrange the tone to use in advance, and set your radio to CTCSS decode mode. Have your friend send your tone when she calls. You won't hear anyone else. But, be sure to turn your decoder OFF before you make a call, or when you answer one, or you might interfere with someone you aren't hearing. Note that some repeaters will not pass these low frequencies, so test the repeater you're planning to use before you count on it as a signal path. Some repeaters will pass the higher tones, but not the lower tones. DTMF (Dual Tone Multi Frequency, more commenly known as Touch- Tone) is used all over Amateur Radio for autopatching and remote control. Many new radios are coming equipped with touch-tone decoders and a mode called "paging." Again, with a DTMF decoder you can silently monitor a busy channel. But this time, instead of listening for a subaudible tone, your radio is waiting for a specific sequence of touch-tone digits. Once again, please turn off your decoder before making a call -- that "quiet" channel may have been busy for hours! DCS is a digital form of CTCSS. Instead of sending a continuous audio tone however, it transmits a low level digital signal. DCS sends a fixed octal digit 4 as the first digit, followed by the three octal digits shown in the table The code words are 23 bit long strings. 12 bits of octal code followed by 11 bits of CRC. Each bit is 7.5 msec in length, for a total of 172.5 msec. Although it looks like there should be 512 codes available, there are only 83 possibilities. This is to prevent a codeword that is misaligned as it is serially shifted into the decoder, to match one of the other codes.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||