|

|

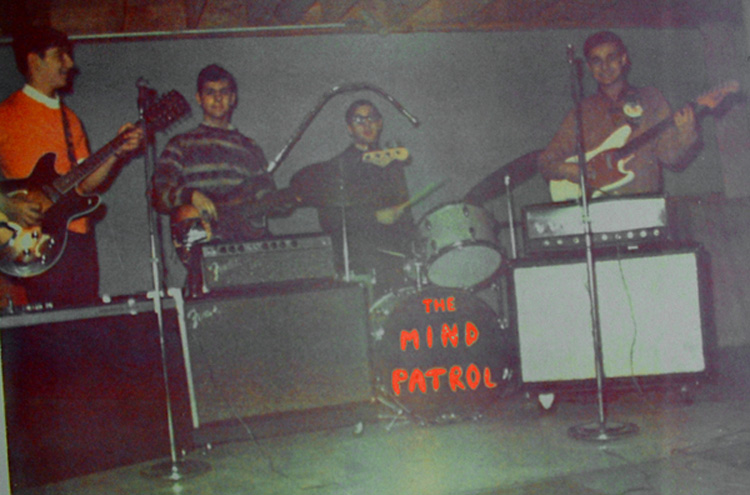

The Last Act Of

THE MIND PATROL

|

The dark, claustrophobic hallways of Central Catholic High School stank of generations of boys crammed into steam-heated, ancient classrooms. It was there that I first met Philip Antone and his brother Tom. They were enduring one of the frequent public bragging sessions conducted by a classmate, Joe Castricone. Like me, Joe was a 14 year-old Freshman, but that didn't stop him from telling anyone who'd listen that he was the greatest rock drummer in all of Lawrence, Massachusetts. When he found out that I played drums too, there was no shutting him up. I was invited to a jam session held at the Antone brothers basement one Saturday. There, Philip and Tom played their guitars with a studied air, striving for subtle nuances of musical phrasing. By contrast, Joe played as loud as humanly possible and without concern for anything. He slammed into flashy rolls and paradiddles at every opportunity, twirling his drumsticks in mid-air like a carnival juggler. Every time the Antone brothers got a tune on its feet, Joe's overpowered drumming quickly brought it to its knees. The sheer effort of pounding himself into a solo position on every song soon proved exhausting, and he'd had enough. He announced he was going home to shower and get ready for some kind of heavy dating action. The Antones didn't seem to mind when I sat down at Joe's drum set. What's more, their hitherto tentative plunking seemed to gain confidence when I backed them up. Free from the tyranny of Joe Castricone, they swept through a half-dozen tunes, and our musical personalities merged into a pretty fair-sounding whole. When we stopped an hour later, the Antones Dad was watching us from the basement stairs. "I've been listening for a while now and you guys never sounded better. Hey, where's Joe Castricone?"

Within a month, we'd built up a repetoire of 20 or so songs and gained a bass player, Mike Fusco. He lived two houses down from the Antones and had a station wagon that would come in handy for equipment transport once we got going. It became obvious that none of us could sing well enough to carry the band. I remembered a guy from the Salem-to-Lawrence bus who could sing just like Eric Clapton if he tried. His name was Tom Blouin, and there was a story going around that while on a blind date he opened the car door and fled without a word, leaving some poor girl stranded at the intersection of Main and Broadway. Like Fusco, Tom was 17, and a senior at Central Catholic. He fit nicely with our little band. The question of a name for the group remained unanswered. Fusco was reading Orwell's "1984" in English Literature and mentioned the "Thought Police". The image was appealing and psychedelic, and I offered a variation: "THE MIND PATROL". We didn't know anything about drugs and had only vague notions about free love, but the name "Mind Patrol" was as cool as anything we'd ever heard, so we instantly adopted it.

Finally we decided that it was time to play out. The Antone's Dad presented us with five matching wide paisley ties. Fusco said he might be able to obtain Nerhu jackets for us at some point. The fact that Mr. Antone acted as our official manager was accepted without discussion simply because he'd gotten us a job playing at a dance in the city of Lawrence a week before Christmas, 1967. St. Anselm's Orphanage sat on a high hilltop, and the tire chains on our two heavily loaded station wagons spun as we skidded up the steep driveway. A heavy, wet snow had begun to fall that afternoon, and by 7 PM all roads were waist-deep in the stuff. The nuns who ran the place assured us that "young people" would indeed show up to attend their Friday night dance. They escorted us to the room where we'd make our musical debut. An altar and some other holy stuff was pushed away in the corners, safe from the coming onslaught of acid rock and sin. It generally took us about a half-hour to set up; a lot of touchy cables and wires, heavy speaker boxes to shift around, microphone problems, and the ritual nailing-down of the bass drum. I had installed twin spikes on the front of the drum to get good bite on the floor and prevent it from slowly creeping away during a song. They would leave their mark on a number of linoleum and oak floors until the secret of laying a carpet square underneath was discovered. Fusco tweaked knobs on his Fender Bassman amplifier until he heard glass windowpanes vibrate, while the Antone brothers busied themselves with threats and petty squabbling, usually about which one's guitar was out of tune. Tom Antone was diagnosed as being slightly tone-deaf, yet he insisted that his guitar be used as an exclusive reference standard. He'd spend the afternoon in his room making sure, through obsessive adjustments, that his instrument was in perfect tune. Once, Philip, fed up with this practice, secretly detuned a string on his brother's guitar just before a performance. A heated argument erupted but Tom Antone held firm, compelling the others to conform their instruments to his sour string. Tom Blouin had no equipment to set up or musical instrument to worry about so he usually hung out with Mr. Antone or went exploring by himself. By the time it was 8 PM, an honest-to-God New England blizzard raged outside. Inside St. Anselm's Hall we struck the opening chords of Wilson Pickett's "Mustang Sally" for a dozen or so kids who'd miraculously appeared out of the winter storm. It wasn't so surprising when you thought about it. Faced with spending a weekend indoors in Lawrence, Massachusetts, most high-school kids would gladly brave arctic conditions for some kind of diversion. Several teen girls wiggled earnestly on the dance floor while a number of boys stared at them from the sidelines. It was always the same. The most unattractive slob of a guy was the best dancer, leaving his more carefully-groomed but timid companions to watch while he enjoyed the attentions of every girl in the place. It took a little over an hour to play our batch of twenty 3-minute songs: Top 40 favorites from now-defunct hit-makers like the Strawberry Alarm Clock, Cream, and The Beau Brummels, and a few ancient standards like "Louie Louie", "Wipeout" and "Moonglow". During our break we argued about what to do next. Nobody had figured on the necessity of having any kind of plan, assuming we'd just play until we were done, and then leave. The Antone brothers wanted to start the list over again from the top. Fusco suggested we put on some records and pantomime. Tom Blouin eyed the exit door. Desperately, we began improvising basic, 3-chord progressions. They had the advantage of sounding vaguely familiar and lasted about fifteen minutes each. Finally, we reprised "Louie Louie" and ended the night with a spirited version of "Havah Nagilah".

We played the Merrimac Valley school-dance circuit for the next few months: Lawrence High School, Central Catholic High School, the Moose Lodge, the Knights Of Columbus. The $300 per night we were paid split five ways to $60 apiece. We took some of our earnings and bought a massive PA system; two coffin-sized speaker cabinets that amplified everything within several blocks and transformed Tom Antone's carefully-tuned guitar work into garbled harmonic chaos. And we finally did obtain the Nehru jackets from Fusco's source. They turned out to be white cafeteria busboy coats that somebody had dyed a sickening shade of orange. The last act of the Mind Patrol was to enter a citywide "Battle Of The Bands". The prize was $100 and 8 hours of recording time at a local guy's home studio. The night of the Battle was the biggest crowd we ever played for. We locked in combat with a half dozen suburban garage bands just like us, with names like the "Sounds Reflection", the "Chameleons", and the "Here They Are". To our utter surprise, we won the grand prize. But our stunning triumph soon bred discontent. A major rift developed in the band. I can't recall what the dispute was about, but it climaxed with Mike Fusco and I breaking the lock on the Antone brother's basement door and removing our equipment while they were attending their Grandmother's funeral. A long series of accusations and spiteful behavior followed, with neither faction willing to admit they were wrong. The Antones took the $100 and formed a new group called "Truth" and it's success eventually paid both their college tuitions. Mike Fusco and I ended up with the free recording studio time. The name of the group we assembled is forgettable, except that the lead singer's name was "Cubie", and together we recorded a 45 RPM single that gathered dust in our closets for 37 years. Hear The Mind Patrol's rare, 45 rpm record, "Sad Little Girl"

|