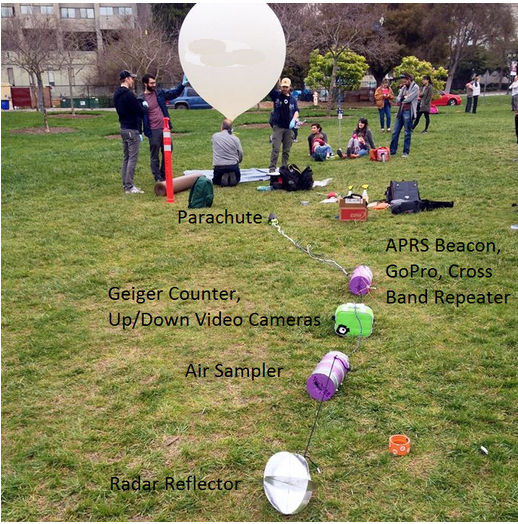

Saturday, March 18, 2017 ~ 10 am: Okay, so it's not really "a day" of ballooning as lots of preparation is required before hand. There were many meetings in the weeks leading up to the launch where technical logistics were hashed out. But the big event is the launch, chase, and (hopefully) recovery, which do all take place on a single day. In fact, one of the most important parts of the planning does not occur until just before the launch - namely, predicting where the balloon is going to go and where the balloon is going to come down. The factors influencing these things are in constant flux and are best considered and analyzed right before you let go of the balloon. So at around 10 am that analysis was going on while a small group of us assembled at Memorial Grove on the UC Berkeley campus and an ever increasing group of interested onlookers gathered around to see what we were doing. All the items in the payload were assembled and roped together, the helium canister (very heavy despite its light contents) was dragged over to the launch site, and the filling of the balloon began.

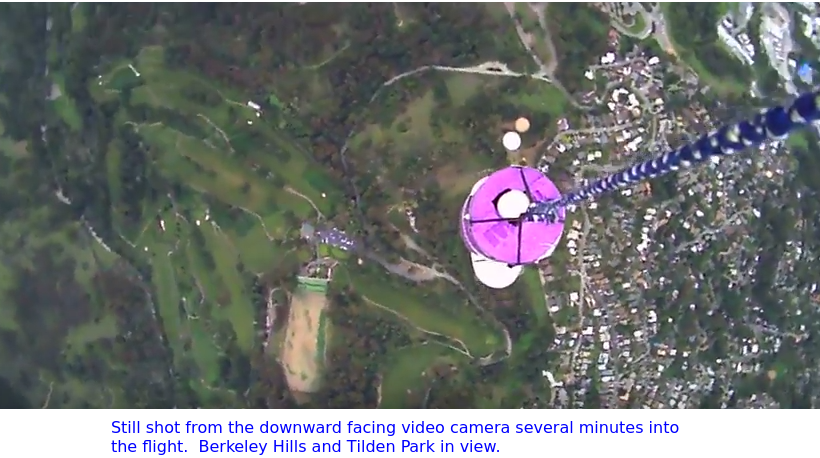

~ 10:30 am: With the requisite amount of helium in the balloon we were ready to launch. The entire assembled crowd joined in the countdown, we let go of the balloon and watched it soar above the campus. The balloon was equipped with a still camera taking one picture every 0.5 seconds, a downward pointing video camera, and an upward pointing video camera.

~ 10:45 am: With the balloon in the air it was time to head to the chase vehicles and begin the chase. The predicted landing site was just southeast of Folsom Lake, a bit over 100 miles northeast of Berkeley, up Interstate 80 to Sacramento and then east on Highway 50 toward Folsom Lake. It would take us just about as long to drive there as it would for the balloon to land so there was no time to lose. Three vehicles were involved in the chase. All were equipped with vhf/uhf radios for communicating with each other, APRS beaconing radios to report their position for others to see, and a laptop to watch the APRS tracks on a map.

~ 11 am: All three chase vehicles were now heading toward Folsom Lake and in full pursuit of the balloon. There was lots of chatter on the crossband repeater and the higher the balloon got, the better the coverage. We were actually concerned about using up the battery on the repeater before the balloon touched down, so we asked for people to keep their transmissions short. But the repeater worked really well with nearly full quieting on all signals. Stations from as far south as Santa Cruz were easily working the repeater when a good altitude was achieved. In my truck, Martin (W6MRR) had a radio/TNC with a 5/8 wave mag-mount antenna on the roof. He was glued to his laptop screen watching the APRS tracks of the balloon as we drove. We were able to receive all the beacons directly off the air and map our position, the other chasers and the balloon's using APRSIS32 software. Jack (K6JEB) was in the back seat monitoring the radio traffic on the repeater. We seemed to be keeping pace with the balloon. When the APRS reported the balloon at 100K feet Martin started to look closely for indications the balloon had started its descent (i.e., it had burst). He was also trying to mentally recalculate where it would come down. The burst point is quite important as the balloon velocity (in a horizontal plane) really picks up as it descends into the jet stream. So knowing where it has burst gives a lot of information about where it will ultimately land.

~ 12:30 pm: Time was really whizzing by, not the typically tedious drive to Sacramento. The whole way we were fixated on where the balloon would come down. Although we'd done all we could to ensure it would land somewhere unpopulated but accessible, you never know for sure. Would it land in a suburban development or even on top of someone's house? Would it land in the middle of Folsom Lake and be unretrievable? Or would it be stuck in a tree on some steep cliff side? Pondering these possibilities and monitoring the APRS signal made the drive fly by (the drive home was not nearly as exciting).

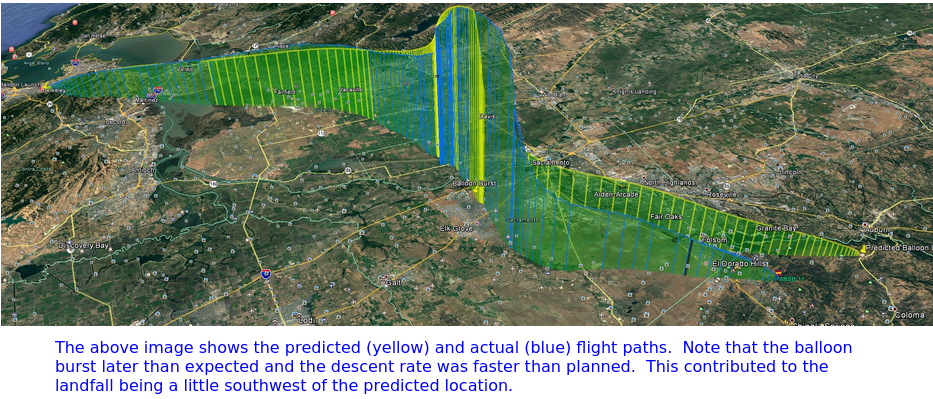

We were about 30 miles east of Sacramento, now on Highway 50, when the APRS showed the balloon starting its descent. This information was shared with everyone listening in on the repeater. The balloon was almost directly overhead of us at this point but should soon be blown quite rapidly in a northeasterly direction so we continued on. Soon Martin noticed that the descent rate (2,000 ft/sec) was about twice as fast as expected. This would mean that the balloon would not travel as far to the northeast as predicted, spending less time in the jet stream. So we pulled off the freeway a bit past the town of El Dorado Hills and took a minute to reassess the landing spot. At that point it looked as if touchdown had occurred and was about 2 miles back (west) of where we'd stopped. So we got back on the freeway heading west for one or two exits and began maneuvering north on surface streets to get as close to the balloon's location as possible.

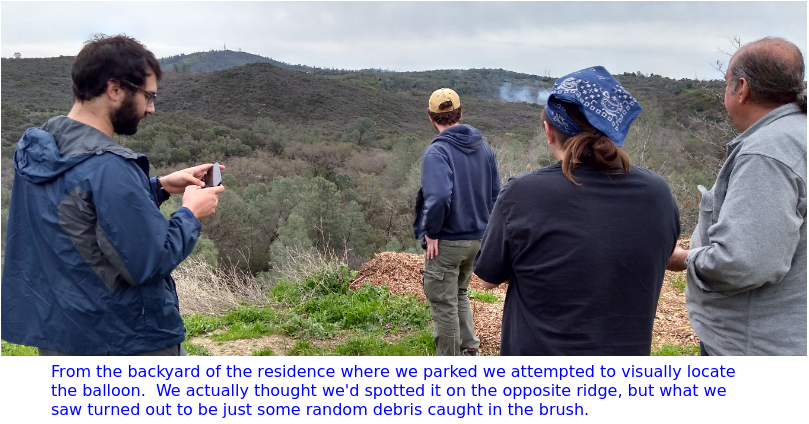

~ 1:15 pm: Looking at the map we determined where we could park on a paved, public access street at the maximum proximity to the balloon. That was along Green Valley Road. We pulled up a long residential driveway to seek permission from the owner to pass through his rather large back yard (several acres) and hike out to where the balloon had touched down. Fortunately we found a very friendly fellow who was more than happy to let us park our cars on his grass and hike down the ridge in search of the balloon. Soon the two other chase cars had joined us and a search party of six began making their way through the brush while two of us stayed behind (in vhf radio contact, of course) and schmoozed with the friendly property owner who milked us for details of exactly what we were doing. It's not your everyday occurrance to have a high altitude balloon land in your backyard and a bunch of college students and ham radio folks descend on you.

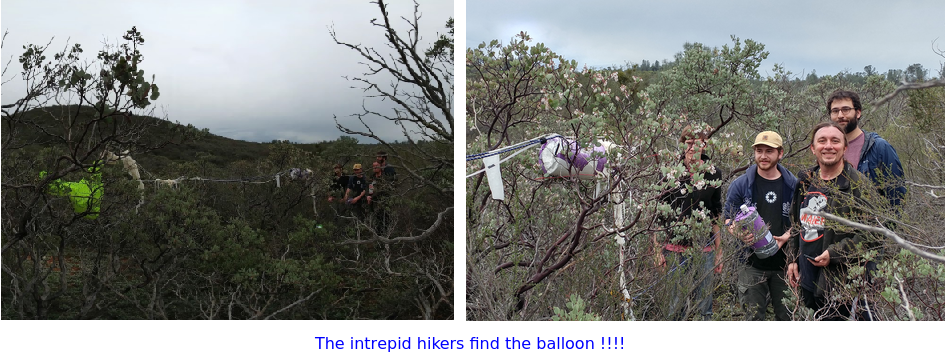

After a little more than an hour we got the call on the vhf radio "we've got a visual on the balloon!" Was it premature to say those infamous words: "Mission Accomplished" ? Nope!

Postscript - The Flight, Experiments and Follow Up: The ascent portion of the flight matched the predictions very closely. The last prediction was run for a 10 AM launch with the actual launch occurring closer to 10:30 AM. The balloon rose higher than predicted and took a brief period to pop. This could be explained by lack of precision in filling the balloon and manufacturing variances of the balloon. The actual descent was more than twice the rate predicted. In examining photos of the landed parachute it appears that the balloon remnants got tangled up where the parachute lines meet the flight line and reduced the diameter of the parachute. We will use more line on the balloon and/or use a balloon cutdown mechanism before the pop next time.

The cross band repeater was a huge success and an interesting DX opportunity on UHF/VHF. Next time it would be good to give hams in a 100 to 200 mile range some advanced notice, giving them a chance to make some interesting long-distance contacts.

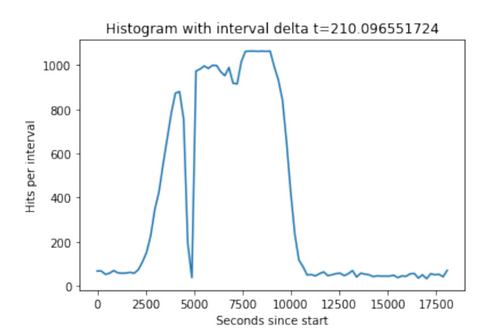

The Geiger counter carried an SD card which recorded strikes and times. The GPS lost fix through most of the flight. The Geiger counter showed increasing radioactivity as it increased in altitude and stayed at nearly full scale for the duration of the flight. The radiation is due to cosmic rays emanating from space colliding with air molecules. A dip at highest portion of the flight was expected as the air density drops off. This may be observed at about 7,500 secs on the plot. The dropout at 5,000 sec was probably a breakdown in insulation and arcing in Geiger counter's high voltage section. Hot glue will fix that.

We developed a successful system for sampling high altitude bacteria. During flight, the system remained sterile by design, and the onboard software worked as intended. The plan was to briefly open up the module to collect a sample at about 60,000 feet. Unfortunately, a contingency we did not plan for was the GPS losing fix. Therefore, the module stayed locked during the entire flight. In future launches, we will use a barometric or generic altimeter instead of (or in conjunction with) a GPS. We will also record flight data to an onboard SD card for future analysis. This will ensure successful sampling and good controls. The loss of GPS fix was likely due to the close proximity between the UHF cross band repeater antenna and the GPS receive antennas. This can be fixed by placing the GPS antennas higher up the flightline and increasing separation.

So some things went perfectly, others not so much. But we can say unequivocally that it was a completely enjoyable experience for all who participated. Stay tuned for the next flight.

73, de W6DEI East Bay Amateur Radio Club