|

|

|

|

|

|

Due to the vanity callsign program, a large number

of

amateurs today have callsigns that were issued to other amateurs in

years past. This is the case with my callsign -

W3DF. I did

not receive this call through the vanity callsign program, but from a

similar FCC program offered in the mid 1970s when extra class license

holders could pick a group of callsigns from available two letter calls

in their call area and obtain one of them. In the 1970s we

did

not have the Internet, so one had to have the latest callbook to find

available callsigns from his call area. This was the case

with me

in late 1976. My "gate" was about to open and I wanted to

change

my call - WA3KOC which was issued to me when I received my novice

license (WN3KOC) in 1968. In early 1977 I submitted my

application with ten callsigns listed in priority order. In

March

of 1977 I received my first choice - W3DF. The significance

of

W3DF is first that "DF" is my initials, and second, "DF" is what I did

while I was in the Navy (1969-73). I was stationed at an HFDF

(high frequency direction finding) station in Scotland while serving a

tour of duty with the Naval Security Group. My Op Sign while I was on duty in Scotland was 'DF'.

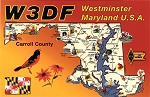

Unknown to me at that time, George Sterling (W1AE) had a home in Baltimore City, not far from me. At that time, he was enjoying retirement in Maine and Florida. During the first few months that I was on the air with the new call, I had people call me thinking that I was George Sterling. After this happened several times I asked some of the local old timers about George and learned that he was well known among old timers in amateur radio, especially in the Baltimore - Washington area. I received several QSL cards from hams who knew George. An example of this is a QSL card from Jules - ZD7YO whom I worked in the 1977 CQWW DX Contest. I hoped that I would run across George on the air but unfortunately that never happened. Since then, I have learned much about George and have compiled his history.

I have a lot in common with George

Sterling. We both were

born in June. We both lived in Baltimore. We both

were/are avid

amateur radio operators. We both served in the

military. I

served in the Navy during Vietnam, and George served in the Army during

WW1 (although he wanted to serve in the Navy). We both were

involved with high frequency (HF) direction finding, George with the

Army Signal Corps and

the Radio Intelligence Division (RID) and I with the Naval Security

Group. We both worked for

the

Department of Commerce during a portion of our careers.

After

graduating from college, I had an opportunity to work for the

FCC. A local ham who worked for the FCC wanted to recruit me,

but I decided to work for the Navy at a research and development

(R&D) laboratory near Washington, D.C. I worked at the Naval

R&D lab until 1992, then took a job with Department of

Commerce/NOAA on a pulse doppler weather radar program, and in 1996 I

took a job at NASA managing the development of instruments for NOAA's

Polar and Geostationay Weather Satellites at the Goddard Space Flight

Center. It

is ironic that George Sterling lived less than 10 miles from

where I grew up in Baltimore, but I never heard him on-the-air.

While researhing his background I learned that he usually operated on

75 meter SSB talking to his friends and RID

colleagues. In Baltimore I did not have room for a 75 meter

antenna, and when I did get on the band with a highly compromised

antenna, I was on CW.

George Sterling's history shows how taking advantage of the circumstances and opportunities of the time led to a career that was unique and will never be duplicated. George Sterling served in every position from Assistant Radio Inspector, Radio Inspector, Inspector In Charge, Assistant Chief Inspector, Field Division Chief, Chief National Defense Operations, Chief Radio Intelligence Division, FCC Assistant Chief Engineer, FCC Chief Engineer and FCC Commissioner. George Sterling is the only amateur radio operator to ever hold all of these positions while working his way up through the ranks of the FCC. He is the only amateur radio operator to be appointed FCC Commissioner.

So here is the history of the first radio amateur who held the call W3DF.

|

|

|

| Peaks Island is located 3 miles east of Portland, Maine in Casco Bay. Ferrys connect the island to the mainland. | Scenic Peaks Island coastline. |

George Edward Sterling was born on Peaks Island located off the southern coast of Portland, Maine on June 21, 1894. He was the son of Wesley Scott Sterling and Annie Cardelia Lotman. George attended public school on Peaks Island. In 1908, the year amateur radio was born, at age 14, George was among the first amateurs to "hit the airwaves" using the new wireless communication medium. In the beginning, amateurs were not licensed. They operated their transmitters on wavelengths generally between 300 to 600 meters (500 KHz to 1 MHz) and picked their own callsigns to identify their station. George probably used is inititals 'GS' for his callsign as most amateurs did during that time. Amateur radio operators were people with a keen interest in the new wireless technology that had been demonstrated by Marconi a few years earlier. The pioneers of amateur radio helped advance the development of wireless through experimentation. Back then, amateurs referred to this activity as advancing the “radio art.” Radio was called "wireless" in the beginning.

|

| 1909: George Sterling, age 15, operating his amateur station. Note the two issues of Popular Mechanics leaning against the wall. |

George got his start into wireless with a couple of his friends. In those early days of wireless everything was homemade or scrounged. The only part of George's original station that was purchased was his headphones. Coils were wound on oatmeal containers and condensers were fabricated from tin foil and paraffin coated paper. Iron pyrite crystals were found in the nearby woods and became the crystal detector for the receiver. Antenna wire was scrounged from abandoned telephone lines they found in the woods. At the time, they thought that the antenna wire had to be bare to let radio waves through, so they removed it by burning it off. To do this they took the telephone line they had found to the cellar of one of his friends, the son of a minister, and started to burn off the insulation. The burning wire got out of control and almost set the house on fire, driving the owner out of the house with the smoke and foul smell.

At age 18, after the passage of the Radio Act of 1912, George received one of the first amateur radio licenses (#106 1AE) issued by the Department of Commerce Radio Service, Bureau of Navigation. The Radio Act of 1912 was the first attempt by the government to regulate amateurs and control the growing interference problem between amateur, commercial, and military radio users. The new law required amateurs to register with the government to obtain a license to operate their transmitter and abide by the newly enacted radio regulations. The new regulations required amateurs to limit the DC input power of their transmitter to one kilowatt and limit their wavelength of operation to wavelengths longer than 200 meters (RF frequency less than 1.5 MHz). At that time it was believed that wavelengths shorter than 200 meters were useless for long distance communication. In those days, long distance communication was considered to be a few hundred miles.

During the pioneering days of amateur radio George operated a spark station with the callsign 1AE. To hear what a spark signal of the period sounded like click here. For those who cannot copy CW, here is the text sent in the audio clip... "AAA AAA Well hams heres a record of the sounds of real wireless as she was spok in the good old days when DX with a KW was about 200 miles and shortwaves were 200 meters and most hams were using the present broadcast band AAA Broadcast stations being non existant iii"

After George graduated from high school, he enlisted in the Maine National Guard and served with the Second Maine Infantry. In 1916 he served on the Mexican border with Company "M" which served as a security force patrolling the Texas border during the Pancho Villa raids on the Mexican border towns of Texas. Later in 1916 George took the test for his commercial ticket at the Boston Navy Yard and took a job as a Marconi merchant marine operator. The 1916 Government Callbook has him listed as 1BH. He doesn't appear again in the Government Callbook until 1924 with the call 3DF.

|

|

|

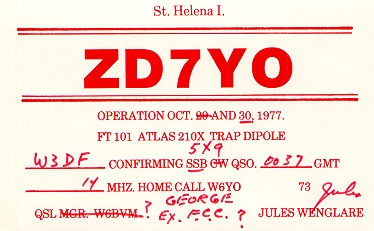

| SS Philadelphia - In 1917 George was a junior wireless operator aboard this ship. | Omnigraph

- the machine used by FCC examiners to give morse code examinations

during the

1910s and 1920s. |

In April 1917 George was a junior wireless operator on the passenger steamship Philadelphia on the Red “D” Line operating out of Brooklyn, New York to Puerto Rico, Curacao and several ports in Venezuela. It was on this same ship, in February 1902, that Marconi had demonstrated wireless communication across the Atlantic Ocean. On April 6, 1917, during a return voyage from South America, his ship received coded orders to paint the ship in Navy colors and sail without lights. The United States had declared war on Germany.

George thought

that his experience as a

radio operator would be better utilized in the Navy, so immediately

upon his return to New York, he went to

the Brooklyn Navy Yard and tried to enlist in the Navy but was told

that he had to be discharged from the Maine National Guard before the

Navy would take him. Not giving up, George then

wrote to the Adjutant General of the state of Maine requesting a

discharge. When the reply did not arrive, he sailed again for

South America. A few weeks later when he returned to New

York, he had orders to

report for duty with his National Guard regiment in Maine.

They

were called into service to guard the railway bridges of the Canadian

National Railway and the Bangor and Ardostook Railway in northern Maine

because of reports that German spies had attempted to blow up

railway

bridges in New York state. While on duty in Maine, he

requested a

transfer to the Signal Corps through his company commander but the

Regimental Commander would not release him.

George thought

that his experience as a

radio operator would be better utilized in the Navy, so immediately

upon his return to New York, he went to

the Brooklyn Navy Yard and tried to enlist in the Navy but was told

that he had to be discharged from the Maine National Guard before the

Navy would take him. Not giving up, George then

wrote to the Adjutant General of the state of Maine requesting a

discharge. When the reply did not arrive, he sailed again for

South America. A few weeks later when he returned to New

York, he had orders to

report for duty with his National Guard regiment in Maine.

They

were called into service to guard the railway bridges of the Canadian

National Railway and the Bangor and Ardostook Railway in northern Maine

because of reports that German spies had attempted to blow up

railway

bridges in New York state. While on duty in Maine, he

requested a

transfer to the Signal Corps through his company commander but the

Regimental Commander would not release him.

In September 1917, the Second Maine infantry set sail to France as the 26th division of the 103rd infantry. Shortly after they landed in Le Fal Le Grand in France, his commander recognized his specialized communication skills and detached him as a Corporal from his squad. After this change of luck, George received orders to Gondrecourt, Headquarters of the French 1st Corps School where he would learn French Army signal tactics. After completing his training he was retained as an instructor of wireless and pyrotechnics.

During his tour of duty at Gondrecourt as an instructor, George was given several interesting assignments which included field testing new infrared signaling equipment, field testing small direction finder loop antennas designed in Major Armstrong’s laboratory in Paris, and field experiments to improve signaling with rockets. Rocketry was an essential part of pyrotechnic signaling, however, his rocket experiments lead to a “close call” with the field artillery and a visit to the Commanding Officer who abruptly ended the experiments.

|

|

|

| Major Edwin Howard Armstrong, WW1 | Sopwith Camel, WW1 |

While instructing a group of aviators in morse code, George revived a boyhood interest in aviation. His interest in aviation had been interrupted a few years earlier by his parents after he had crashed a home made glider while attempting to take it off. After studying the required material and experiencing the thrill of several flights on British Sopwith Camel aircraft, he applied for a commission for second Lieutenant as an "observer,” one who corrects artillery fire by wireless signals from an aircraft. When the endorsements were returned, his Corps Commander had disapproved his request but granted him a transfer to the Army Signal Corps, American Expeditionary Forces (AEF).

The British and French had been successful intercepting, decoding, and locating enemy radio stations and the Germans were using wireless up to the front line. This led the U.S. Signal Corps to organize a section to participate in the same activity. There were a few qualified operators with the French Army to gain experience in this job and George was sent to the front line to help operate the new radio intelligence service.

|

|

|

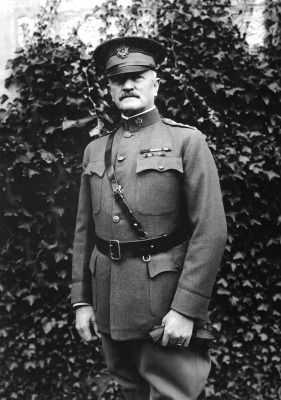

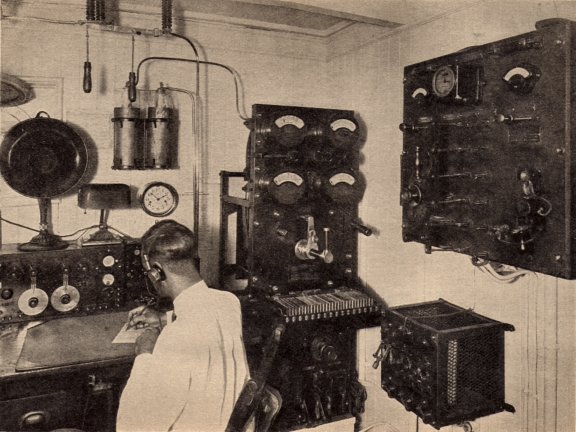

| General Pershing, Commander AEF | The radio room at Chaumont |

After reporting to General Pershing’s Headquarters at Chaumont, George was assigned to a long wave intercept watch to copy POZ (a German commercial station) and a few other long wave stations for a few days until going to the front line where he was assigned to Headquarters Company at Langres, France.

The Headquarters Section was established in French Army barracks outside of Toul which was bombed nightly by the Germans. Having gained his first exposure to vacuum tube transmitters at Gondrecourt, he was placed in charge of the unit's vacuum tube transmitters. Several intercept and direction finding stations were placed in operation and listening posts were established in the trenches to monitor German telephone and ground telegraphy communications. As operations continued, it quickly became apparent that many of the stateside trained signal corps operators were not producing accurate copy, while operators who were amateurs or commercial operators were producing good copy. The decision was made to establish a school near the front line to train operators in German field procedure and how to copy through interference. George was selected to establish and operate the school. The school paid off and was closed after enough men were trained to man the stations around the clock. George was then assigned to prepare mobile intercept and direction finding units for the St. Mihiel drive.Another of George’s assignments in preparation for the St. Mihiel drive was the deployment of transmitting stations in a sector around Nancy which was a few kilometers from St. Mihiel. Each station was given a sheaf of coded messages and the operators were ordered to send them on a carefully worked out schedule around the clock to divert German attention away from St. Mihiel.

During the St. Mihiel drive George had a few close calls with the Germans. On one occasion he and his partner found themselves behind German lines while trying to locate and deliver supplies to the field units advancing with the drive. After delivering the needed supplies they managed to get back to allied territory safely. The St. Mihiel drive took place on September 12-15, 1918 and was a successful battle for the U.S. Army and its allies.

Shortly after the Armistice of November 11,

1918, George,

along with

three other men from his section, received orders to the Officers

Training School in Langres, France. In early 1919 George

graduated as

a second Lieutenant and was given the option to continue active duty in

the Army of occupation or take ten days leave in Nice and first class

passage home as an Army Reserve Officer. After being overseas

for

19 months George elected to go home. For this work he

received a

citation from the Chief Signal Officer of the AEF for excellent and

meritorious service.

Shortly after the Armistice of November 11,

1918, George,

along with

three other men from his section, received orders to the Officers

Training School in Langres, France. In early 1919 George

graduated as

a second Lieutenant and was given the option to continue active duty in

the Army of occupation or take ten days leave in Nice and first class

passage home as an Army Reserve Officer. After being overseas

for

19 months George elected to go home. For this work he

received a

citation from the Chief Signal Officer of the AEF for excellent and

meritorious service.

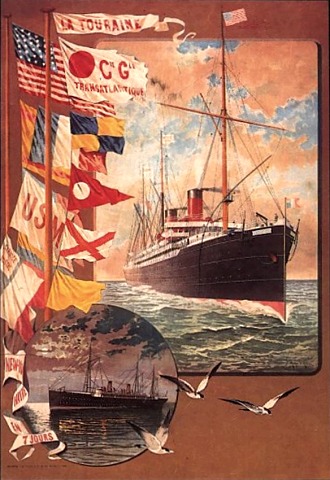

After ten days of R&R in Nice and Monte Carlo, George set sail for home aboard the French ocean liner, La Tourraine. After being away from the sea for so long, he was seasick most of the way home, but did visit the ship’s radio shack on the night before they docked in New York.

While waiting to be discharged at Camp Merritt in New Jersey he visited the Marconi office there which had previously employed him. When he inquired about a job, he was told that being a veteran and having been previously employed by the company gave him no priority and that his name would be placed at the end of the list. George left the office “mumbling in his beard and cursing everybody from McNally down.”

George was discharged from the Army in April

1919 with the rank of Master Sergeant Signal Electrician.

He

went home

to Maine where his parents had moved from Peaks Island to the

mainland. He returned to his old job of learning the family

shoe

manufacturing business and banking, but the call of the sea was too

strong. In November 1919 George went back to sea as a

wireless

operator. After WW1, he does not appear in the Government Callbook until 1924 with the call 3DF in Baltimore, Maryland.

In the early 1920s, wavelengths shorter than 200 meters were pioneered by amateurs and transatlantic HF communication became commonplace. In 1920, amateur vacuum tube continuous wave (CW) transmission was gaining momentum. The principal obstacle to amateur use for CW was the cost and availability of transmitting tubes. Amateurs who were accustomed to using 1 KW spark transmitters could not bring themselves to use a CW transmitter capable of just a few watts of power. After the highly successful trans-Atlantic receiving test of 1921 showed the superiority of CW, spark was prohibited in 1922 due to its wide bandwidth and increasing interference and CW became the norm once vacuum tubes became readily available to amateurs. The first CW transmitters were built with a single five watt vacuum tube oscillator which was keyed directly in the cathode or grid circuit. To hear what a CW signal of the time sounded like click here. For those who cannot copy CW, here is the text sent in the audio clip... "AAA This CW signal is made by one small vacuum tube using 45 volts keying in grid circuit with practically no voltage at key contacts iii This signal is audible only because it was received on an oscillating vacuam"

|

|

|

| 1920s

shipboard

radio station |

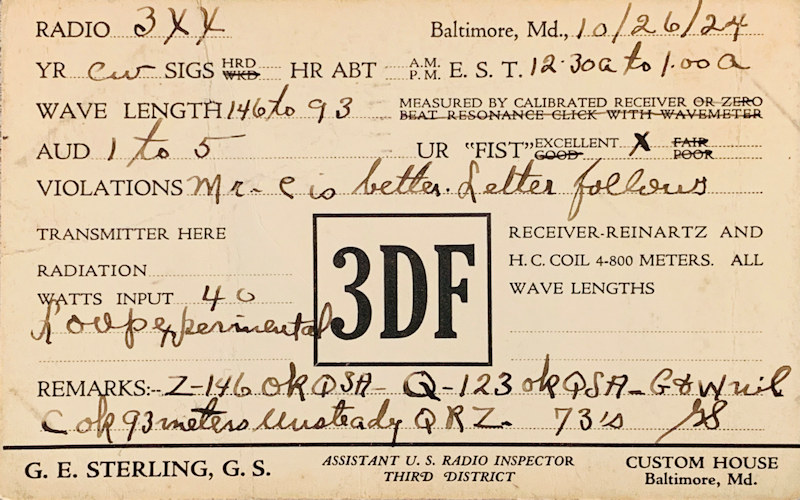

Assistant Radio Inspector Sterling's violation notice. From the collection of N2BTD. |

In

the early 1920s, during a trip to

England as a marine

wireless operator for the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company, George

was blown

off course and fell in love with a beautiful actress and ballet dancer

in London named Margaret Farrey. In 1922 George accepted a

job ashore with

RCA as a radio inspector at the port of Baltimore. There he

made

routine inspections and repairs to shipboard transmitters and converted

shipboard spark sets to vacuum tube CW transmitters.

In

the early 1920s, during a trip to

England as a marine

wireless operator for the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company, George

was blown

off course and fell in love with a beautiful actress and ballet dancer

in London named Margaret Farrey. In 1922 George accepted a

job ashore with

RCA as a radio inspector at the port of Baltimore. There he

made

routine inspections and repairs to shipboard transmitters and converted

shipboard spark sets to vacuum tube CW transmitters.

In June 1923, George was sworn in as a Federal

Radio Inspector

for the

Department of Commerce, Bureau of Navigation in the third radio

district. The third radio district covered Maryland,

Washington,

D.C., Delaware and parts of Virginia, Pennsylvania and New

Jersey. As a radio inspector he was responsible for the

inspection of foreign and domestic shipboard radio

installations.

His other duties included inspection of land, coastal and experimental

stations including broadcast and amateur stations as well as

examination of applicants for all classes of operator licenses from the

third district headquarters at the Custom House in Baltimore City

(Note: I took my amateur exams at the Custom House in 1968, 1969 and

1972).

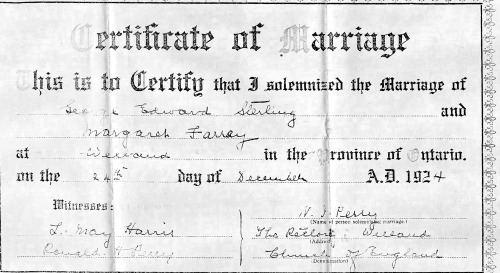

On Christmas Eve 1924, George and Margaret were married in a church in Welland, Ontario. After their honeymoon they took up residence in the Stoneleigh neighborhood near Towson, Maryland just north of Baltimore where they lived until 1937.

|

|

|

| Margaret

Farrey

circa 1920. Margaret was born in 1900 in Manchester,

England. She was an actress and ballet dancer on the London

stage. |

Margaret

was an

actress and

ballet dancer when George met her in London, England in the early 1920s |

In Baltimore, George held the call 3DF from 1924 to 1927, then W3DF from 1928 to 1973. He

attended

night school at Johns Hopkins University and Baltimore City

College. From 1927 to 1936 he worked for the Federal Radio

Commission, the predecessor to the Federal Communications Commission

(FCC), as Radio Inspector in Charge at Fort McHenry for the third radio

district. In 1937 he was promoted to Assistant Chief of the

Field

Division of the engineering department of the FCC in Washington, DC and

moved his residence from Baltimore to Silver Spring, Maryland (Note:

from 1992 to 1996 I worked at the Department of Commerce/NOAA just a

few blocks from his Silver Spring residence). At that time, the

Field

Division

handled the administration of the 21 field offices and monitoring

stations. Prior to the U.S. entering World War II George was

promoted

to

Chief of the Field Division.

|

|

|

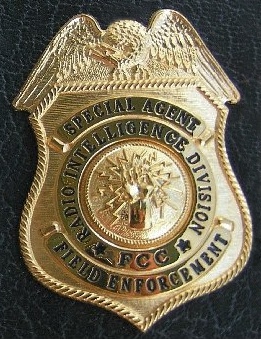

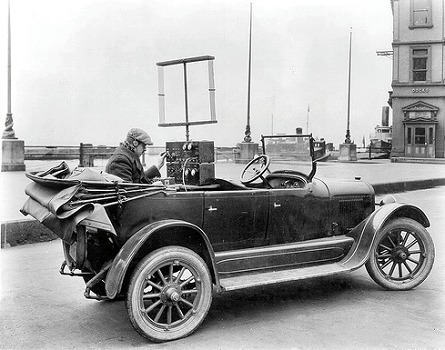

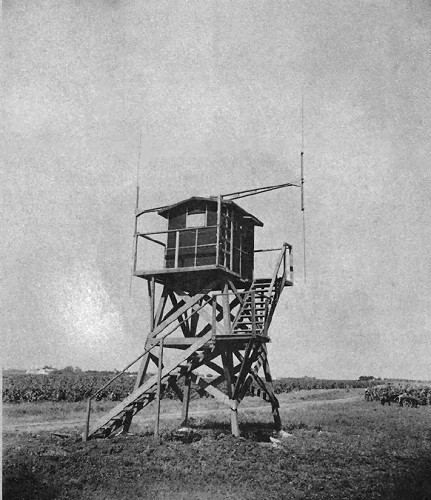

||

| Badge worn by RID agents | Early experimental

DF mobile unit (1930s) |

December 1939 -

Commissioners Thompson, Craven, Chairman Fly, Brown and Case (left to

right) inspect a television receiver. |

In 1939, with the war in full swing in Europe, the State Department knew they were lacking vital war intelligence being exchanged by radio between Germany and South America. In early 1940 they approached the FCC about the monitoring and intercept of this intelligence information. At that time the FCC Field Division had its hands full monitoring domestic operations and had no time to spare for intelligence monitoring.

In the face of the alarming use of radio by Nazi

spies in

Europe and

the increasing need to monitor the use of the radio spectrum at home,

the FCC acted to put the country in a

state of radio preparedness. A plan was prepared to modernize

and

increase the number of monitoring stations and provide mobile units for

at least one station in each of the states to do local investigative

work and pinpoint illegal transmitters and sources of

interference. The plan was submitted to Congress and

approved. In June 1940, President Roosevelt allocated 1.6

million

dollars from the emergency fund for radio defense efforts and

established a new section within the FCC, the National Defense

Operations Section (NDO) to augment the FCC monitoring

network.

George Sterling was appointed to lead this new section of the FCC and

was promoted from Assistant Chief FCC to Chief NDO.

Monitoring officers and radio operators were recruited from industry and the amateur ranks. The nucleus of the staff was taken from the ranks of the Field Division, those men who had gained considerable experience locating the illegal transmitters of rum runners during the Prohibition days, race track touts and tipsters with transmitters trying to beat the bookies, smugglers, and radio pranksters.

|

|

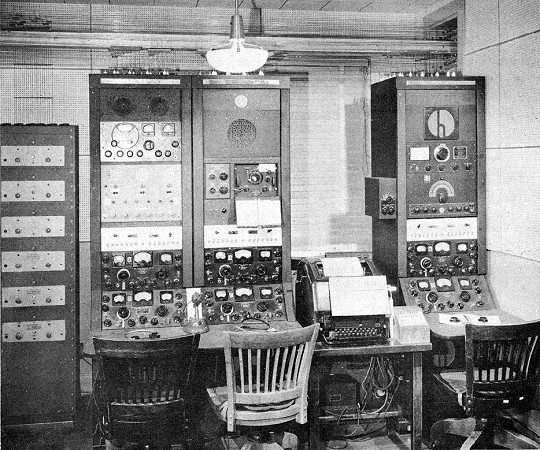

|

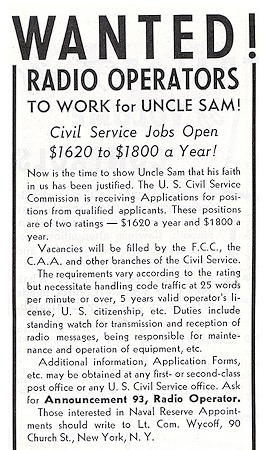

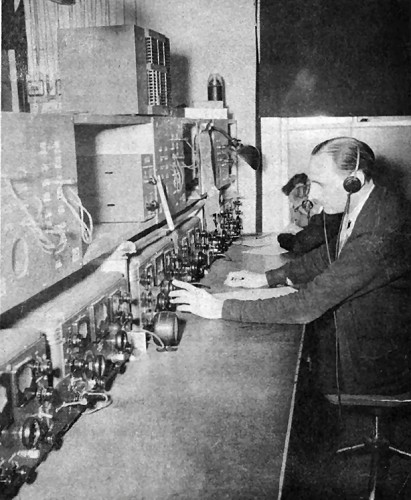

| Intercept position, primary monitoring station Allegan, Michigan. SX-28s stacked above another for the convenience of the intercept officer copying both the spy and control station on different frequencies. Transmitters on the left operated on different frequencies to transmit alerts to the secondary monitoring stations and furnish frequencies and calls in FCC cipher code when a case became active. | The FCC placed this ad in the June 1940 issue of QST for radio operators after Congress approved funding to increase the number of FCC monitoring stations. |

To quickly obtain the needed personnel, George Sterling instructed one of his assistants to search the file cards containing information on licensed amateur and commercial radio operators. More than 500 names were selected from the files and telegrams were sent to those selected offering them positions in NDO. Those positions were radio operator ($1800 per year), Assistant Monitoring Officer ($2400 per year) and Monitoring Officer ($3200 per year). The entire complement of NDO personnel was obtained from the responses to those telegrams. In total, about 80% of the NDO staff were radio amateurs.

NDO monitoring operations began on September 3, 1940. Later that year, NDO was upgraded from a Section of the FCC to a Division becoming the Radio Intelligence Division (RID) and George Sterling became its Chief. The RID charter was to investigate and monitor clandestine radio operations in the United States and it's possessions. As the war progressed, RID took on the task of monitoring clandestine radio transmissions from all over the world including Europe, Africa, South America, and Asia. It also trained military personnel and intelligence agents in radio intelligence, monitoring, and radio direction finding techniques.

Before the war hit the U.S., the FCC's business of

policing the U.S. air waves was accomplished by 8 primary monitoring

stations and 26 mobile units. The FCC policed illegal

transmitters, inspected shipboard and police radios and monitored the

activities of the

nation's amateur radio operators. When the state of national

emergency hit the country prior to Pearl Harbor, the FCC was authorized

to expand its radio

detection facilities.

When the disaster of

Pearl Harbor occurred, the

major part of

RID's expansion was complete and RID was on the job in Hawaii, Alaska,

and on the West Coast. The primary monitoring

stations had

a full

compliment of equipment. Banks of SX-28 receivers,

transmitters,

CW and teletype for inter-station and network communication, Adcock

direction finders, fixed rhombic antennas, and various forms of

recording equipment including mills (typewriters) for manually coping

traffic. Mobile units became an

integral

part of each secondary station equipped with Hudson automobiles with

receivers and loop direction finding antennas used for mobile close-in

surveillance.

When the disaster of

Pearl Harbor occurred, the

major part of

RID's expansion was complete and RID was on the job in Hawaii, Alaska,

and on the West Coast. The primary monitoring

stations had

a full

compliment of equipment. Banks of SX-28 receivers,

transmitters,

CW and teletype for inter-station and network communication, Adcock

direction finders, fixed rhombic antennas, and various forms of

recording equipment including mills (typewriters) for manually coping

traffic. Mobile units became an

integral

part of each secondary station equipped with Hudson automobiles with

receivers and loop direction finding antennas used for mobile close-in

surveillance.

The monitoring stations and mobile units were

linked

via radio communication. They were organized into three

major networks based on radio intelligence centers in Washington, DC.,

San Francisco, and Honolulu. When "on a case" fixing the

location

of a source of radio signals, the three networks were combined into one

network directed from Washington.

When the expansion was complete there were four new primary monitoring stations in Texas, Alaska, Hawaii and Puerto Rico. There were 12 primary monitoring stations, 60 secondary stations, and 90 mobile units. The Field Division operated the primary monitoring stations performing their normal regulatory and enforcement duties while the personnel of the RID monitored for intelligence transmissions in separate sound proof rooms. During the war, on average, six thousand individual bearings were taken per month resulting in more than 800 fixes, each requiring at least four bearings for a reliable long range fix.

|

|

|

| FCC Adcock direction finding antenna at the Lexington, KY monitoring station (circa 1940s). | Interior view of an Adcock direction finder shack circa 1940s. |

|

|

|

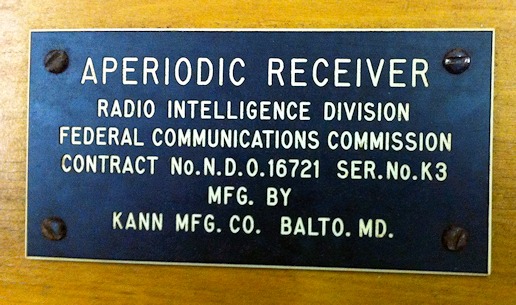

| Aperiodic receiver developed by RID and used by the Office of Strategic Services (OSS-the predecessor of the CIA), Navy and Army during WWII. | SSR-201 Aperiodic Receiver name plate. |

George Sterling appointed Charles Ellert (W3LO), a Johns Hopkins engineering graduate as Technical Advisor. Under Ellert's direction, studies were conducted to improve the accuracy of the Adcock direction finders. The result of this work produced bearings with far greater accuracy than had been previously obtained from commercially purchased equipment. Since RID had neither the men nor the money to provide continuous surveillance of clandestine operations, it became necessary to develop a radio receiver that would respond to any signal within the communications spectrum and be insensitive to all but the strongest signals. From these requirements an aperiodic receiver was developed and patented by two RID engineers, James Veatch and William Hoffert. The aperiodic receiver, known as a watchdog, was used in mobile units providing surveillance at fixed locations such as the Japanese internment camp and was later used by the Navy and Office of Strategic Services (OSS was the predecessor of the CIA). RID was first to employ the panoramic receiver in counter espionage operations. The panoramic receiver permitted continuous observation, on a cathode-ray-tube screen, of the presence and relative strength of signals within a wide frequency range.

|

|

|

|

|

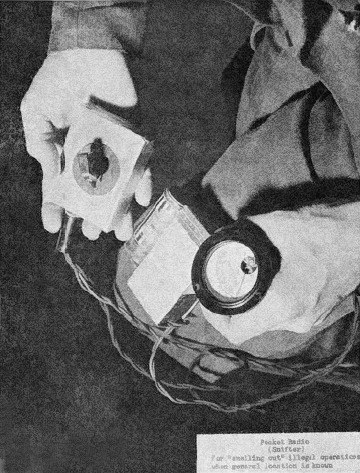

| The Snifter used by RID agents to locate the precise location of a transmitter in buildings and other close quarters. It was concealed under a coat with the meter wired down the sleeve and the antenna strung down the pant leg. | Tom Cave, monitoring officer in charge at the RID intercept station in Scituate, R.I. The Scituate station was instrumental in tracking down many clandestine stations during World War II. | Adcock direction finding antenna at the Scituate, RI monitoring station. |

|

|

|

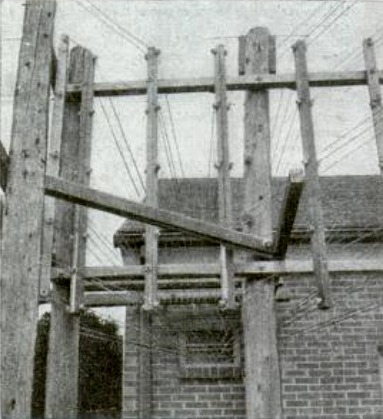

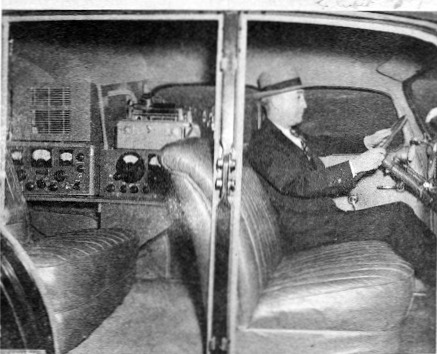

|

|

| Feedline terminations routed into a primary monitoring station. Most primary monitoring stations had an array of rhombics to cover 360 degrees in azimuth. | Internal view of RID prowl car used to intercept signals and locate sources of interference. The loop did not show while the car was cruising but only when taking a bearing. Equipment included an SX-28, dictaphone recorder and other receivers covering 75 Kc to 300 Mc. | RID mobile intercept and direction finder unit used to home-in on clandestine radio activity. |

Under Charles Ellerts supervision, the ‘Snifter’ was developed. The ‘Snifter’ was a simple receiving device contained in a small pack worn around the waist with an antenna strung down the inside of the operators pant leg. To monitor the received signal, either a hearing aid or a meter held in the operator’s hand was used. The ‘Snifter’ was used to pinpoint the location of a transmitter when casing corridors of hotels, apartment houses, or on the roof of buildings containing many antennas. Another RID achievement was the use of the selectable sideband adapter developed by James McLaughlin. It was fitted to the Hallicrafters SX-28 receivers which were the workhorse of RID. The selectable sideband receiver was used to minimize jamming.

|

|