In 1946, as the FCC was allocating new radio

bands for police agencies, Los Angeles was the

site of a test/demonstration of the comparative

quaities of the 30-40mc, 72-76 and 152-162mc

bands for mobile transmitting. The latter group,

today known as the "VHF High band,"

showed great promise in built-up areas. Click here

to see an interesting report of the 1946 tests of

the different radio bands, and AM vs FM,

conducted by L.A.P.D. for the California APCO

chapters.

|

In 1948, LAPD's mobile "talk-in"

channels were shifted up to this "VHF"

band, in the 154-155

mc segment, at which

time the venerable KMA367 callsign was first

assigned. Several of those original VHF

frequencies are still in use more than half a

century later, most notably Frequency 9 - 154.83 mHz - which is today's

"Tac 1 - Hotshot" channel. At the same time the

department began converting the mobile

frequencies from AM to FM modulation, which

reduced electrical interference and improved

reception.

|

However, rapid

growth, tight budgets, and automakers' changing

car electrical systems from 6-volts to 12-volts

all slowed the process significantly. For a

number of years until the late 1950s, and there

were both FM and AM radios operating in 6- and

12-volt police cars. The radio shop at 5th &

San Pedro Streets had to struggle to maintain

parts (and proficiency) to keep all those radio

models functioning.

|

1949 also saw LAPD's

motorcycle fleet starting to use two-way radios.

Until that time motor officers had been using

receiving-only radios, as there were few

transmitters available which could operate on

their motors and handle the vibration.

|

|

|

A Traffic Enforcement

Division Sergeant - sans

helmet - checks out his

fancy new rig

|

As the city grew in

the early 1950's, and radio traffic increased, a

second dispatch frequency of 2366 kc was added for

dispatching to the Valley, Harbor, and West

LA-Venice, using callsigns of KQJO, KQJP

and KQJN,

respectively. San Fernando Valley dispatching was

by then being handled from a separate facility at

"Valley Services Division" in Van Nuys.

|

RTO at her console

in the new Police Administration Building, 1955.

Click to enlarge |

When the new

"Police Administration Building" (later

renamed "Parker Center") opened in

1955, Communications Division was one of the

first facilities to begin operation.

Interestingly enough, though the space was more

than three times as large as the previous cramped

space in the north wing of City Hall, the general

operation continued much as it had for many

years. It is said that many of the operators'

"status boards" were literally carried

over from City Hall and installed in the

horse-shoe shaped "mike room" consoles.

Calls continued to be taken by policemen at the

complaint board, and were still sent by a fast

conveyor belt into the radio room.

|

In a major

restructuring in 1964 and 1965, the dispatch

"talkout" frequencies were changed to

the 158-159 mHz frequency range,

and RTOs eventually had five frequencies (A, B,

C, D and E) for dispatching to

their respective divisions. Though apparently

unused, the old 1730 kcs

frequency remained licensed to LAPD until a June

26, 1978 modification of the "KMA367"

authorization.

|

RTO and status-board at

Parker Center, circa 1968

|

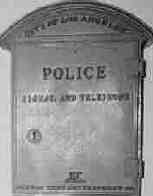

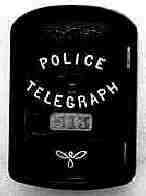

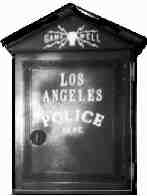

The

Gamewell

Rain

or shine

|

| The

"Gamewell" call-box

system has been in use in Los

Angeles for more than a century.

Beginning in the 1890s, the boxes

were utilized for hourly call-ins

by officers in the field, who all

had fixed posts or walked

footbeats. Callboxes were located

in all patrol divisions, usually

installed at intersections where

two or more beats met. When

practical, boxes were located

along Division

boundaries for efficiency and

economy. Early on, the

policeman would open the box and

pull a handle to identify himself

to the city operator downtown. If

there were no calls for him, he

would receive a

"two-bell" signal and

be on his way. Three bells,

however, meant there was a call

for him; he would pick up the

receiver and listen to a message

telling him only to "See the

man (or woman)," and the

location - nothing more.

Such cryptic

information was certainly not

conducive to officer safety! A

young policeman from the early

1910-era later wrote that this

practice added to his misgivings

about his new career. "It

seemed to me the operator should

have learned more, and the

policeman answering the call

should at least have some idea of

what to expect. I had yet to

learn that most police calls were

brief and lacked detail. The

important matter on any call was

the address.1"

( Nearly a

hundred years later plenty of

patrol officers have muttered the

same complaint, though the

operators and the equipment in

use today are immeasurably

better, and the information

available by radio or MDT is

tremendously improved ).

By about 1925,

the system had been redesigned.

There were over 500 callboxes

throughout the city, each

equipped with a Western Electric

telephone handset, and they were

now connected to the local

Division station rather than to

City Hall. At his appointed time

each hour, the officer would pull

a handle to identify his callbox

to the Divisonal operator, and

then give his name. If there were

any calls or messages pending for

him, they would be given,

otherwise he would simply be

"marked off" as having

called in for the hour, and would

receive the two-bell "you

are clear" signal.

In the 1970s, the

remaining private-circuit

"Gamewell" system was

integrated into the city's

"Centrex" telephone

system; the antiquated

street-corner phone-sets were

replaced with push-button phones,

and the two plug-and-cord

Gamewell consoles in

Communications Division were

removed.

|

|

|

NEW! 1950s "Daily

Training Bulletin"

I've been fortunate enough to

obtain a nearly-new copy of the 1953/54 "Daily

Training Bulletin" of the LAPD. In just over half a

century, many things have changed so very much...while

others, not a bit. Click here to see the section on

Radio Communications ... it's quite a "hoot! "

|