Satellites and Cruising – A

Winning Combination

Allen F. Mattis, N5AFV, [email protected]

Abstract

Operating FM LEO satellites from a cruise ship is relatively easy. However, advance planning and preparation are needed to obtain the necessary amateur radio licenses, prepare for obtaining permission to operate on the ship, and select and become familiar with the equipment. Those who operate on the satellites from a cruise ship soon find out how much fun it is to be called by dozens of amateur radio operators pursuing new grid squares for the ARRL VUCC satellite award. Anyone planning to operate from a cruise ship should begin their preparations at least several months before the cruise.

Requirements for

Maritime Amateur Radio Operation

The information available on the ARRL web page regarding

maritime operation by

The text of Section 97.11 of the FCC rules is quite clear and to the point:

“97.11 Stations aboard ships or aircraft

(a) The installation and operation of an amateur station on a ship or aircraft must be approved by the master of the ship or pilot in command of the aircraft.

(b) The station must be separate from and independent of all other radio apparatus installed on the ship or aircraft, except a common antenna may be shared with a voluntary ship radio installation. The station's transmissions must not cause interference to any other apparatus installed on the ship or aircraft.

(c) The station must not constitute a hazard to the safety of life or property. For a station aboard an aircraft, the apparatus shall not be operated while the aircraft is operating under Instrument Flight Rules, as defined by the FAA, unless the station has been found to comply with all applicable FAA Rules.”

The two primary requirements for operating amateur radio while on a ship are proper amateur radio licensing and obtaining permission to operate.

Licensing on

Foreign Flagged Vessels

The basic rule regarding licensing for amateur radio on a ship is that operation in international waters requires the operator to have an amateur radio license from the country in which the vessel is flagged. If the vessel is not in international waters, but in the territorial waters of a nation, it is necessary to have an amateur radio license from that nation in order to operate amateur radio from the ship. Fortunately, a number of international treaties and conventions make foreign licensing relatively easy for US amateur radio operators. The American Radio Relay League (ARRL) web page (http://www.arrl.org/FandES/field/regulations/io/) has a great deal of information on these international agreements, as well as on reciprocal licensing (Mattis, 2003).

European Conference

of Postal and Telecommunications Administration (CEPT)

The European Conference of Postal and Telecommunications

Administration (CEPT) agreement T/R 61-01 gives

International Amateur

Radio Permit (IARP)

The Inter-American

Telecommunication Commission (CITEL) has adopted an agreement for an

International Amateur Radio Permit (IARP) similar to CEPT, but it includes eleven

countries in North and

An International Amateur Radio

Permit (IARP) authorizes amateur radio

operation in eleven countries in North and

Reciprocal Licensing

In addition to CEPT and IARP, the

One downside of reciprocal licensing is that most of the permits

cost $20 or $25 a year, and personnel checks or cash are not accepted for

payment. US Postal Service money

orders are accepted in most, but not all, nations. The Cayman Islands is an example of a

nation that does not accept US Postal Service money orders; however, the Cayman

Islands will accept a cashier’s check from a

Another drawback to reciprocal licensing is that some nations take a

long time to process an application.

My application for a reciprocal permit in

The ARRL web page does a good job of providing information on

reciprocal licensing; however, the information that is posted on the ARRL web

page is not always up to date. For

example, the name of the agency that issues amateur radio licenses and permits

in the

Finally,

there are some places visited by cruise ships where you can operate with a

Obtaining Permission to

Operate

The stipulation in Section 97.11 of the FCC rules that states “installation and operation of an amateur station on a ship or aircraft must be approved by the master of the ship” is another hurdle that faces those who wish to operate amateur radio on board a cruise ship. In years past, the captain of the vessel would delegate authority to approve such requests to the radio officer. However, the international regulation requiring all ships at sea to monitor the international CW distress frequency of 500 kHz was dropped in 1999 and many cruise lines no longer have radio officers. Most cruise ships have replaced the radio officer with a communications officer whose responsibility includes maintaining both the information technology (IT) network and the radio systems on board the ship.

It used to be possible to meet with the radio officer on a cruise ship (MacAllister, 1997), and this often made it easier to obtain permission to operate. With the tighter security imposed because of the increase of terrorism in the world, it is usually no longer possible to speak with the communications officer. Requests to operate amateur radio on a ship today are generally made in writing, and submitted to the purser’s desk for forwarding to the communications officer. After my first cruise, I learned that it is better to write a letter requesting permission to operate before leaving home, and to print out several copies to take along on the cruise. A neat legible typed letter that has been carefully worded has a better chance of obtaining approval to operate than a letter written by hand while standing at the purser’s desk with little advance thought given to the wording.

The primary concern when deciding whether or not to allow amateur radio operation on board a ship is that of safety and preventing possible interference to any apparatus or systems installed on the ship. It is very unlikely that any cruise ship would allow a passenger to put up an antenna and a run of coaxial cable. We all know that operation of radio transmitters sometimes causes RFI, and that is probably why some cruise lines forbid passengers to operate any kind of two-way radio on board their ships. Fortunately, the UHF/VHF bands employed by FM LEO satellites lend themselves to the use of low power and handheld antennas, and seldom result in RFI.

Many of today’s communication officers do not have the in depth knowledge of radio theory possessed by the radio officers of the past, and when requesting permission to operate it is necessary to address any negative perceptions regarding amateur radio that they may have in their mind. It is important that several points be clearly made in the written request to operate. The letter I have developed after several cruises requests permission to operate a small low-power handheld amateur radio on board during the cruise. I state that the radio is very similar to the Family Radio Service (FRS) radios used by many passengers, but operates on the 145 MHz VHF and 435 MHz UHF amateur radio bands. I tell them that I typically operate for very short periods of time, usually 10 to 15 minutes three or four times a day. I do not tell them that I will operate through a satellite or give them any details they do not need to know. The cruise line does not want any passenger to do anything that will disturb other passengers, so I state that I use a small headset with a microphone when I operate the radio so that I do not disturb other people. I usually end my letter by stating that I have operated this equipment on cruises in the past and that it did not cause any problems.

The time it takes to receive a response after a request to operate

amateur radio has been submitted varies with both the cruise line and the

ship. On one cruise with Princess

Cruises, written approval to operate amateur radio was delivered to my

stateroom eight hours after I submitted my request at the purser’s desk. On a later cruise with Princess I turned

in my written request at

In the past two years, some amateur radio operators who sailed on Carnival Cruise Lines have reported that they did not receive a reply to their written requests to operate amateur radio while on the ship. What most amateur radio operators do in this situation is to assume that if after reading the request the communications officer hasn’t notified them that it is not permitted, they are allowed to do it. I experienced a similar situation on a cruise with Royal Caribbean International a year ago. My written request was returned to my stateroom the next day by ship’s mail with no comments or markings on it. Since the communications officer knew I wanted to operate amateur radio and he didn’t notify me that I couldn’t operate, I assumed it was permitted.

The Celebrity Cruise line reportedly has a current policy of not allowing passengers to operate any kind of two-way radio on their ships. Even though the promotional material that Celebrity sends to passengers and prospective passengers does not mention the policy, my travel agent was told by a Celebrity agent that they would confiscate any amateur radio equipment they found on board one of their ships.

Sometimes approval is given to operate amateur radio on a cruise

ship, but with restrictions. For

example, one radio officer approved my request to operate, but not at a full

power of five watts. He was

concerned about possible interference to the ship’s radios on the 156 MHz

VHF marine band. During that cruise

I was careful not to transmit near any antenna on the ship that looked like it

was used for VHF. In some

instances, radio amateurs are asked not to transmit during critical periods

such as when the ship is entering or leaving a harbor, or docking (MacAllister,

2000). On my last cruise, I chose

not to transmit while passing through the

In some ways, obtaining permission to operate is probably the single largest obstacle facing those who wish to operate amateur radio on cruise ships. There is always the possibility that once you have obtained the necessary licensing and boarded the ship you will not be able to operate.

N5AFV enjoying ideal maritime mobile

operating conditions in the Caribbean.

(Photo by KE4RQZ )

Selecting

Equipment and Preparing for Operation

When most people think about operating amateur radio on a

cruise ship, they visualize someone sitting in a comfortable deck chair in the warm

sun sipping a cool drink between or even during contacts. Only a small percentage of amateur radio

satellite contacts made from a ship resemble that mental image. The fact is that the operating

conditions on the open deck of a ship at sea are often hostile in nature. First of all, there is usually a

strong wind. If the ship is moving

at approximately twenty knots into a twenty five knot wind there will be a

fifty mile per hour wind blowing across the deck. If you have ten to fifteen foot seas the

ship will be rocking significantly.

Also, the deck may be wet from ocean spray, and it could even be

raining. It may be cold; I have

experienced temperatures in the 40-to-45 degree Fahrenheit range on ships in

the northern

It is important to keep these operating conditions in mind when selecting the equipment to be used for operating the amateur radio satellites on a cruise. The equipment should be light weight, water resistant, and operate on self-contained batteries. I also take the approach that the equipment should not draw undue attention to the operator. If just one other passenger makes a negative comment to the ship’s crew about the amateur radio operation, it is possible that the communications officer or captain would shut down the operation. On my last cruise another passenger watched me operating a satellite pass and asked me what I was doing. I thought it would be a good opportunity to talk up ham radio and AMSAT, so I explained what I was doing. The passenger’s first comment after I finished my explanation was to ask about people’s right to privacy on the satellite. There was no way he would believe that I had authority to talk over a satellite, and he was convinced that I was illegally listening to telephone calls. If he had reported the incident to the ship’s crew my maritime mobile amateur radio operation would possibly have been shut down.

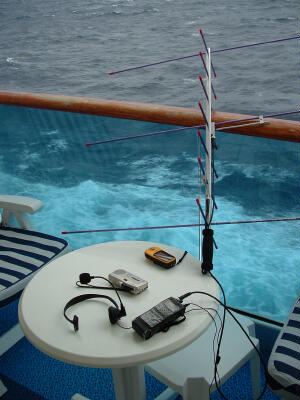

Equipment spread out on the table of

the veranda in preparation to work a pass.

Because I feel that it is important to keep a low profile and not attract attention, the Icom W32A HT with a Premier (Pryme) AL800 telescoping antenna has become my choice of equipment for operating FM LEO satellites on a cruise. Other satellite operators such as Lee Devlin, K0LEE, (Anonymous, 2000) and John Sheets, N8QGC, have used the Arrow antenna on cruises, and I also used it on a cruise where I operated from veranda of my stateroom. An Arrow antenna is a little cumbersome to carry around when assembled, and it takes a minimum of several minutes to assemble. It is difficult to match the portability of an antenna like the Premier (Pryme) AL800 that fits in your pocket and only takes a couple of seconds to attach to your HT and be ready for use. Soifer (1999) has had success using the MFJ-1717 16-inch rubber-coated dual-band antenna for working FM LEO satellites, and MacAllister (1997) used the similar Diamond RH77 15-inch rubber-coated dual band antenna on his cruise. On my last cruise, I was able to switch back and forth between the Premier (Pryme) AL800 and MFJ-1717 antennas while making contacts on SO-50 and AO-27. I found that both antennas performed acceptably; however; the Premier (Pryme) AL800 appeared to provide better reception than the MFJ-1717. I usually take an MFJ-1717 along on my cruises as a back up antenna.

While I use an Icom W32A HT on cruises, other brands and

models that have full dual-band capability may also be used. For example, Soifer (1999) has used the

Yaesu FT-50R HT and Sheets (1999) has used the Alinco DJ-G5T for portable

operation on the FM LEO satellites.

A larger rig like the Yaesu FT-817 with self-contained batteries may

also be used for portable operation (Glasbrenner, 2005). Gene Marcus, W3PM, operated on the

amateur radio satellites from the Queen Elizabeth 2 in the

Besides the transceiver and antenna, other equipment is needed to efficiently operate on board a ship. A GPS unit is essential to know the maidenhead grid square in which the ship is located, as well as the direction the ship moving. It is necessary to know the direction the ship is moving to determine which side of ship to be on in order to work a low elevation satellite pass. I have already mentioned that I use a headset so my radio will not disturb other passengers; an inexpensive MFJ-288I headset has served me well. I have also found that a small, voice-activated tape recorder allows me to record the call signs of the stations I work. In order to keep the set up simple, the recorder does not record from the radio, but records only my voice. After the satellite pass, I transcribe the information on the tape recorder into a hard copy log. Other miscellaneous items to remember to take along include extra batteries for the GPS unit and tape recorder, and the user’s manual for your radio. I sometimes take a few pieces of backup equipment along such as a speaker microphone or extra headset, a trickle battery charger, and few basic tools like black electrical tape, screw drivers and pliers.

Each amateur radio operator on a cruise ship must decide the best way for them to obtain pass predications for the satellites. I try to travel light on cruises, so I do not take a Palm Pilot or lap top computer with me. Because I know the itinerary of the cruise ship before I leave home, I am able to print out pass predictions in advance for the entire cruise. Most ships have Internet access available to passengers for a fee, and on the rare occasions when it appeared that my pass predictions were not correct I was able to go to the Heavens Above web site (http://www.heavens-above.com/) and obtain the information I needed.

It may also be desirable to have copies of the receipts showing when and where you purchased your radio and any other expensive pieces of gear. This documentation may be needed if you plan to take these items ashore at a stop or when you go through customs upon return. I generally put together a small three-ring binder containing these items along with a few maps, my amateur radio licenses and permits, the pass predictions, log sheets and any other related items I feel I may need.

It is also a wise plan of action to thoroughly inspect and check out each piece of equipment before you leave. If something needs repair, you will have time to do it or have it done. On one cruise I packed my Arrow antenna without testing it, and when I assembled it on the ship and tried to work an SO-50 pass I could hear the satellite, but I could not get into the bird. The duplexer in the Arrow handle was defective on the two meter side, and the Premier (Pryme) AL800 I had packed as a backup antenna became my primary antenna for the cruise.

One way to check out the equipment is to make contacts with it before the cruise. My usual procedure consists of using my W32A HT and AL800 antenna to make 75 to 100 satellite contacts during the month prior to the cruise. On the final day of practice operation five days before my first cruise I was working a satellite pass and received two reports of low audio. Testing indicated that the microphone in my MFJ-288I headset was not working properly, and I replaced the headset before leaving. Making practice contacts before the cruise also prepares you for operating on the ship. It is easier to make contacts in the dark or under hostile conditions when you are used to using the equipment. Also, it is essential that an amateur radio operator have experience operating on the satellites before attempting a cruise operation, and a “newbie” or new operator can gain that experience in a few weeks of practice operation.

Summary

Operating amateur radio satellites from a cruise ship is not difficult if proper advance planning and preparation have been done. Licensing usually takes at least several months, and a carefully worded written request prepared in advance increases the likelihood of receiving permission to operate. Selection and thorough testing of the equipment to be used should not be left to the last minute. An amateur radio operator attempting to operate on FM LEO satellites during a cruise should have prior satellite operating experience. If these steps are followed, operating FM LEO satellites from a cruise ship can be a very rewarding experience.

References

Anonymous, 2000,

(Volume 23, Number 4), p. 26.

Glasbrenner, Andrew, 2005, A Short Introduction to Using Your FT-817 and Arrow for

SSB Satellite Demonstrations: The AMSAT Journal, January/February

(Volume 28, Number 1), p. 8.

MacAllister, Andy, 1997, Cruising for AO-27 on the Carnival Sensation: 73 Amateur

Radio Today, HAMSATS column, March, p. 60.

MacAllister, Andy, 2000, Cruising for Satellites: 73 Amateur Radio Today – Special

HAMSATS issue, October, p. 22-28.

Mattis, Allen, 2003, Prior planning - key to a successful DX cruise: The AMSAT Journal,

May/June (Volume 26, No. 3), pp 24-26, (reprinted from Worldradio, 2002, April,

p. 18-21).

Sheets, John, 1999, AO-27 Satellite Operations are Possible on a Small Budget: The AMSAT

Journal, May/June (Volume 22, Number 3), p. 22-23.

Soifer, Ray, 1999, AO-27: An FM Repeater in the Sky: The ARRL Satellite Anthology,

p. 4.11-4.12, (reprinted from QST, January, 1998, p. 64).

Published in Proceedings of AMSAT-NA 23rd Space Symposium, pp. 128-138.

E-mail - [email protected]