|

(found on http://www.e31.net/engines_e.html)

The number of cylinders is not the primary reason for engine smoothness,

another important factor is the way the engine is constructed, if it's an

inline-, V- or boxer-engine. Those concepts will be discussed here.

The One-Cylinder Engine (general)

A one cylinder four-stroke engine delivers power only in the working/combustion

cycle (the compression cycle even needs power) and therefore, measured by the

rotation of the crankshaft, only every 720°. To smoothen this rather jerky

power delivery one needs a flywheel (which lessens the engine's responsiveness)

- or more cylinders.

An increase in cylinders does mainly mean more working cycles per crankshaft

rotation and therefore a smoother power delivery.

With four cylinders there is a working cycle every 720° / 4 = 180°, with eight

every 90° and with twelve even every 60° (3: 240°, 5: 144°, 6: 120°, 10: 72°).

But now there are the vibrations caused by the moving parts inside the

engine. I will restrict this to pistons and connecting rods in order to keep it

simple and because they are the main source of vibrations.

Rods and pistons move up and down without counterweights and of course there is

movement to the side as well, but that only for the rods which don't weigh so

much.

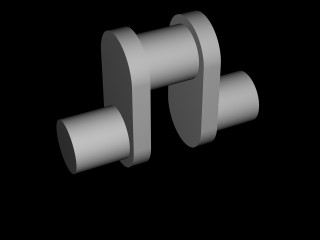

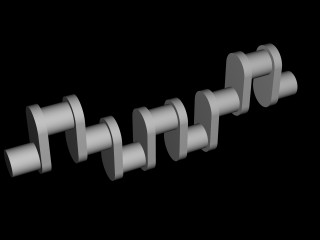

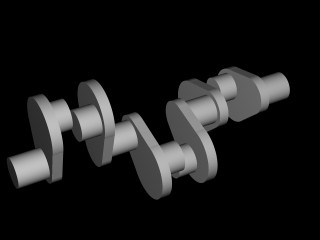

The crankshaft of a one cylinder engine.

For simplification the counterweights

for the crank pins have been left out. |

The Inline-Two Engine

A two-cylinder engine has a working cycle every 360°, which means that both

pistons have to be in the same position and move in same direction all the time.

The vibrations therefore are twice as bad as with a one-cylinder engine because

the forces of both cylinders add up. This design has the most vibrations and is

therefore the less used one.

The crankshaft of an inline-two engine. |

The Inline-Three Engine

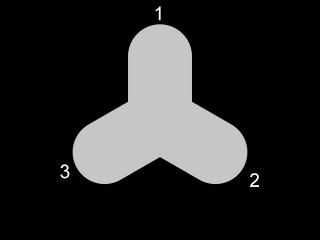

Every 240° there is a working cycle. The frontal view shows that no matter at

what angle the crankshaft is, the center of gravity stays in the middle always

so that no vibrations are generated. Almost. The image and the calculation do

not take the third dimension into account. The pistons are not arranged in a

plane but in line. While there is an upward force being generated by piston and

connecting rod in the front most cylinder, there is a downward force in the rear

one. Because these forces act on different ends of the engine, there is

end-to-end vibration, around the center cylinder.

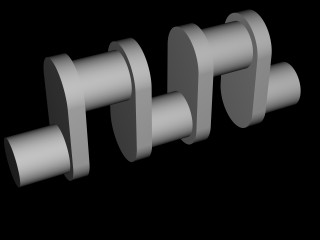

Crankshaft of a inline three cylinder engine. |

Frontal view of crankshaft. |

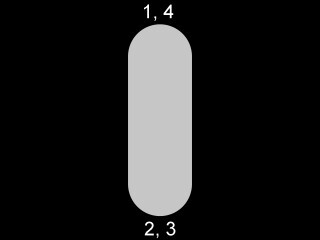

The Inline-Four Engine

Now things get complicated. Although it seems that a four cylinder engine is

free of vibration, it is not.

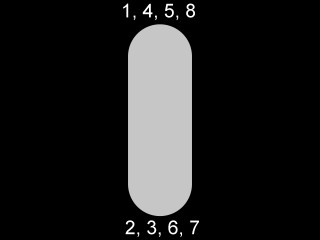

An inline four engine fires every 180° which means that always two pistons are

in the same position and move in the same direction. Because of the symmetrical

arrangement there is no end-to-end vibration as with the three cylinder engine

(piston 1 and 4 plus 2 and 3 are pairs).

The problem is the vertical movement. At first glance it seems that the forces

generated by the first piston are cancelled by the second and the forces of the

third are cancelled by the fourth. But that is not the case!

As you can see in the picture, pistons which are moving up, are moving at

different speeds than pistons that are moving down. So there are vibrations

again which have to be cancelled by balancer shafts.

The crankshaft of an inline four engine. |

Frontal view of crankshaft. |

Forces generated by pistons and rods which are moving up and

down do not cancel themselves but result in 'second order forces'. |

The Inline-Five Engine

This type of engine is mentioned only to be complete, because it is not necessary

for understanding engine smoothness. Except vibrations from end to end (like a

three cylinder engine) a five cylinder engine runs smoothly.

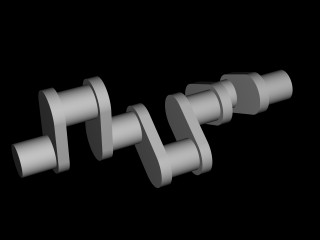

The crankshaft of an inline five engine. |

Frontal view of crankshaft. |

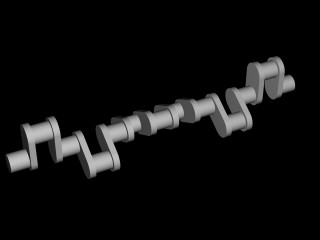

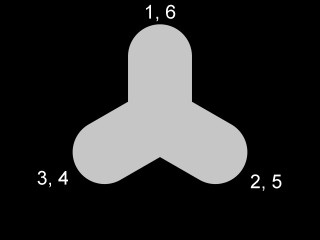

The Inline-Six Engine

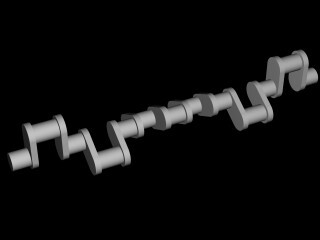

As you can see an inline six engine consists basically of two mirrored three

cylinder engines. That results in two sorts of vibrations (around cylinder #2

and #5) which cancel themselves. So there isn't even end-to-end vibration.

Because the crankshaft is identical to the one of a three cylinder, only twice

as long and with twice as much pistons, here as well is no change of the center

of gravity and no forces are generated, neither horizontal nor vertical ones.

That is the reason why inline six cylinder engines run so smoothly.

The crankshaft of an inline six engine. |

Frontal view of crankshaft. |

The V6-Engine

The V6 is a special kind of V-engine. It is normally the case that two pistons,

one for the left and one for the right cylinder bank, share a crank pin. In a V6

the crank pins have to be split and shifted in order to avoid vibration between

banks.

There are two kinds of V6 engines with different V-angles in use, 60° and 90°.

The 90°-V6 has a 30° crank pin shift (see picture), the 60°-V6 60° shift.

Just as the three cylinder engines, a V6 generates end-to-end vibration, so a

balancer shaft is needed. Thus V6-engines are inferior to inline six engines

concerning smoothness, despite having the same number of cylinders.

So why use V engines? Although twice as much camshafts are needed, the higher

friction, the lack of smoothness and the higher production cost, the V6 uses

much less space, which helps saving costs in other places and allows front wheel

drive (which saves further costs).

Crankshaft of a 90°-V6 with 30° pin shift. |

Frontal view of crankshaft. |

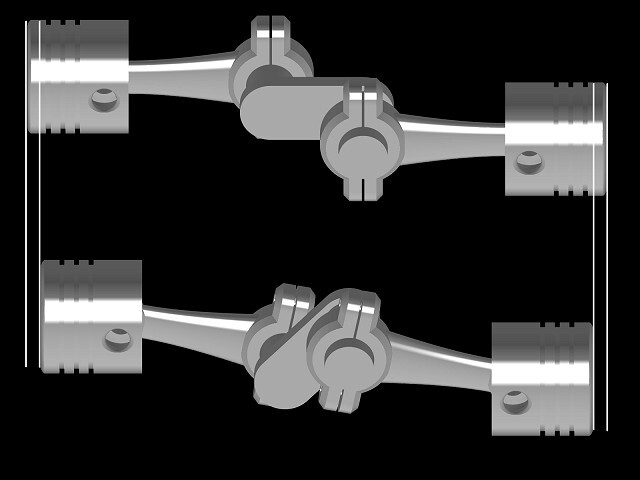

The V8-Engine

There are two types of V8s which differ by crankshaft. The V-angle is always 90°.

The two types are called cross-plane (crank pins at a 90° angle) and flat-plane

(crank pins at 180°). V8 engines have the advantage of not being in need of

split crank pins in order to avoid vibrations between cylinder banks.

With a cross-plane V8, however, the last cylinder is not in the same position as

the first, so there is end-to-end vibration again. That can be solved by adding

counterweights to the crankshaft which cancel the forced created by the pistons.

That is possible only in a V-engine with a V-angle of 90° and without split

crank pins. These counterweights, fitted to an inline engine, would move to the

side when the piston moves up or down and therefore generate additional

vibration. But in a 90° V-engine there are pistons on the same crank pin which

move exactly into the opposite directions of the counterweights (because of the

bank angle) and their forces can be cancelled. Cross-plane V8s are therefore

running quite smooth but because of the heavier crankshaft they are not as revvy.

Flat-plane V8 engines do not have those problems. They are also more

responsive because of less rotational inertia. That increases maximum rpm and

top-end power. In addition the crank case can be smaller which lowers the center

of gravity.

But why are the flat-plane engines used in sports cars only if there are so many

advantages? That's because of the crankshaft itself, the disadvantage of the

flat-plane type. As you can see, the arrangement of crank pins is identical to a

four cylinder engine which means there are also vibrations, only stronger, as

basically two inline-four engines are running simultaneously. In sports cars

those vibrations are reduced by using very lightweight pistons and connecting

rods. That is of course expensive and because ride quality isn't too important

either, the rough characteristics (compared to a cross-plane) are tolerated.

Because of the crankshaft, the sound of such an engine is the one of two four

cylinder engines. A (typical American) cross-plane burbling cannot be achieved.

The crankshaft of a cross-plane V8-engine. |

Frontal view of crankshaft.

|

The crankshaft of a flat-plane V8-engine. |

Frontal view of crankshaft. |

The V12 Engine

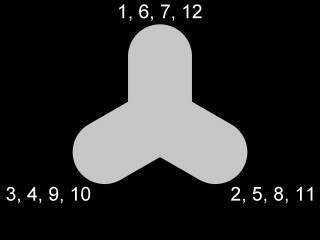

The V12 is said to be the most sophisticated engine design, being free of

vibrations and running smoothly. But so does an inline six. Now what is the

difference between those two concepts concerning smoothness, as even the

crankshafts look alike?

Let us return to the one-cylinder. It was said there, that an engine's power

delivery occurs in 'jerks', every time a combustion takes place. And that is the

secret of a V12: the smoothness is increased by more combustions per crankshaft

revolution.

The crankshaft of a V12 engine. |

Frontal view of crankshaft. |

Boxer-Engines

In boxer engines the pistons are not aligned upright or in V-shape, but lie

horizontally opposed. This type of engine not only achieves an extraordinary low

center of gravity but also runs perfectly smooth and free of vibrations -

regardless of number of cylinders.

As you can see in the following picture, a pair of pistons are not only

always in the same position but also move with the same speed - only into

different directions so that all vibrations are cancelled.

A boxer-engine runs always smoothly. |

|