|

|

|

|

|

|

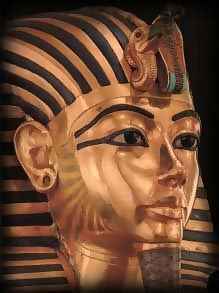

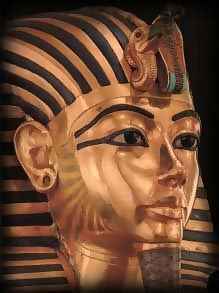

The final wall of the sealed burial chamber of the boy pharaoh was breached for the first time in 3,000 years on 17 February 1923. Archaeologist Howard Carter whispered breathlessly that he could see `things, wonderful things' as he gazed in awe at the treasures of Tutankhamun. As Carter, together with fanatical Egyptologist Lord Carnarvon, looked at the treasures of gold, gems, precious stones and other priceless relics, they ignored the dire warning written all those centuries ago to ward off grave robbers. In the ancient hieroglyphics above their heads, it read:

`Death will come to those who disturb the sleep of the pharaohs.'

The final blow of the excavators' pick had set free the Curse of the Pharaoh. Lord Carnarvon had never taken lightly the threats of ancient Egypt's high priests. In England before his expedition had set out, he had consulted a famous mystic of the day, Count Hamon, who warned him:

'Lord Carnarvon not to enter tomb. Disobey at peril. If ignored will suffer sickness. Not recover. Death will claim him in Egypt.'

Two separate visits to mediums in England had also prophesied his impending doom. But for Carter and Lord Carnarvon, who had financed the dig culminating in history's greatest archaeological find, all thoughts of curses and hocus-pocus were forgotten as they revelled in the joy of the victorious end to the dig. The site of Luxor had escaped the attentions of grave robbers down through the centuries, and the treasure-packed tomb was a find beyond compare.

The accolades of the world's academics rained down on him and his team. The praise of museums and seats of learning as far apart as Cairo and California was heaped on them. Carnarvon revelled in the glittering prize of fame - little knowing that he had but two months to enjoy the fruits of his success. On 5 April 1923, just 47 days after breaching the chamber into Tutankhamun's resting place, Carnarvon, aged 57, died in agony - the victim, apparently, of an infected mosquito bite. At the moment of his death in the Continental Hotel, Cairo, the lights in the city went out in unison, and stayed off for some minutes. And if further proof were needed that it was indeed a strange force that was at work, thousands of miles away in England, at Lord Carnarvon's country house, his dog began baying and howling - a blood-curdling, unnatural lament which shocked the domestic staff deep in the middle of the night. It continued until one last whine, when the tormented creature turned over and died.

The newspapers of the day were quick to speculate that such eerie happenings were caused by the curse, an untapped source of evil which Carnarvon and Carter had unleashed. Their sensational conclusion was reinforced when, two days after Carnarvon's death, the mummified body of the pharaoh was examined and a blemish was found on his left cheek exactly in the position of the mosquito bite on Carnarvon's face. Perhaps this could have been passed off as coincidence had it not been for the bizarre chain of deaths that were to follow.

Shortly after Carnarvon's demise, another archaeologist, Arthur Mace, a leading member of the expedition, went into a coma at the Hotel Continental after complaining of tiredness. He died soon afterwards, leaving the expedition medic and local doctors baffled. The deaths continued. A close friend of Carnarvon, George Gould, made the voyage to Egypt when he learned of his fate. Before leaving the port to travel to Cairo he looked in at the tomb. The following day he collapsed with a high fever; twelve hours later he was dead.

Radiologist Archibald Reid, a man who used the latest X-ray techniques to determine the age and possible cause of death of Tutankhamun, was sent back to England after complaining of exhaustion. He died soon after landing.

Carnarvon's personal secretary, Richard Bethell, was found dead in bed from heart failure four months after the discovery of the tomb. The casualties continued to mount. Joel Wool, a leading British industrialist of the time, visited the site and was dead a few months later from a fever which doctors could not comprehend.

Six years after the discovery,12 of those present when the tomb was opened were dead. Within a further seven years only two of the original team of excavators were still alive. Lord Carnarvon's half-brother apparently took his own life while temporarily insane, and a further 21 people connected in some way with the dig, were also dead. Of the original pioneers of the excavation, only Howard Carter lived to a ripe old age, dying in 1939 from natural causes. Others have not been so fortunate.

While countless Egyptologists and academics have tried to debunk the legend of the curse as pure myth, others have continued to fall victim to it's influence...

Mohammed Ibrahim, Egypt's director of antiquities, in 1966 argued with the government against letting the treasures from the tomb leave Egypt for an exhibition in Paris. He pleaded with the authorities to allow the relics to stay in Cairo because he had suffered terrible nightmares of what would happen to him if they left the country. Ibrahim left a final meeting with the government officials, stepped out into what looked like a clear road on a bright sunny day, was hit by a car and died instantly.

Perhaps even more bizarre was the case of Richard Adamson who by 1969 was the sole surviving member of the 1923 expedition. Adamson had lost his wife within 24 hours of speaking out against the curse. His son broke his back in an aircraft crash when he spoke out again. Still skeptical, Adamson, who had worked as a security guard for Lord Carnarvon, defied the curse and ave an interview on British television, in which he still said that he did not believe in the curse. Later that evening, as he left the television studios, he was thrown from his taxi when it crashed, a swerving lorry missed his head by inches, and he was put in hospital with fractures and bruises. It was only then that the stoic Mr Adamson, then aged 70, was forced to admit: `Until now I refused to believe that my family's misfortunes had anything to do with the curse. But now I am not so sure.'

Perhaps the most amazing manifestation of the curse came in 1972, when the treasures of the tomb were transported to London for a prestigious exhibition at the British Museum. Victim number one was Dr Gamal Mehrez, Ibrahim's successor in Cairo as director of antiquities. He scoffed at the legend, saying that his whole life had been spent in Egyptology and that all the deaths and misfortune through the decades had been the result of `pure coincidence'. He died the night after supervising the packaging of the relics for transport to England by a Royal Air Force plane.

The crew members of that aircraft suffered death, injury, misfortune and disaster in the years that followed their cursed flight. Flight Lieutenant Rick Laurie died in 1976 from a heart attack. His wife declared:

`It's the curse of Tutankhamun - the curse has killed him.'

Ken Parkinson, a flight engineer suffered a heart attack each year at the same time as the flight aboard the Britannia aircraft which brought the treasures to England until a final fatal one in 1978. Before their mission to Egypt neither of the servicemen had suffered any heart trouble, and had been pronounced fit by military doctors. During the flight, Chief Technical Officer Ian Lansdown kicked the crate that contained the death mask of the boy king, `I've just kicked the most expensive thing in the world,' he quipped. Later on disembarking from the aircraft on another mission, a ladder mysteriously broke beneath him and the leg he had kicked the crate with was badly broken. It was in plaster for nearly six months.

Flight Lieutenant Jim Webb, who was aboard the aircraft, lost everything he owned after a fire devastated his home. A steward, Brian Rounsfall, confessed to playing cards on the sarcophagus of Tutankhamun on the flight home and suffered two heart attacks. And a woman officer on board the plane was forced to leave the RAF after having a serious operation.

The mystery remains. Were all those poor souls down the years merely the victims of some gigantic set of coincidences? Or did the priestly guardians of the tomb's dark secrets really exert supernatural forces which heaped so much misery and suffering on those who invaded their sacred chambers - and exact a terrible punishment on the despoilers of the magnificent graves of their noble dead?

The most intriguing theory to explain the legend of the curse was advanced by atomic scientist Louis Bulgarini in 1949. He wrote:

`It is definitely possible that the ancient Egyptians use atomic radiation to protect their holy places. The floors of the tombs could have been covered with uranium. Or the graves could have been finished with radioactive rock. Rock containing both gold and uranium was mined in Egypt. Such radiation could kill a man today.'