A news item published in The New Indian Express (Chennai Edition).

Tuesday, November 2, 1999

Pros failed, Hams saved the day

New Delhi, Nov 1: No hightech satellite phones; not the emergency terminal activated by the Department of Telecommunications but a set of amateur radio communiacators saved the day for Orissa today.

When every government effort to restore communication seemed to be failing, a group of the volunteers belonging to National Institute of Amateur Radio (NIAR) finally made a breakthrough in the small hours of the Monday when they successfully established a contact with the Chief Minister's residence in Bhubaneshwar from Delhi.

At around midnight, the team of volunters, mostly students, succeeded in making it to Giridhar Gamang's residence in the State Capital from Hyderbad.

Within an hour, the Ham operators set up a temporary radio station at the Chief Minister's residence and started operations in the high frequency bandwidth.

Till evening about 50 important official messages had been sent across to Chief Minister's residence by the temporary station in Delhi.

"Our volunteers in Bhubaneswar will shortly disperse in the affected districts to establish communication," said Bharati Prasad, additional director of NIAR.

Courtesy - Davindar Kumar

Its a medium that becomes a lifeline at the time of disasters and Orissa, circa 1999, has been no different.

Out of a smallish black box called a trans-receiver has come salvation for an entire state suddenly rendered innocent of all communications links. You sit at this box. In an innocuous corner of a faceless, file-lined office in Delhi's Orissa Niwas, and marvel at the miracles it can achieve.

From midnight of October 31 when they set set up a station at the Cheif Minster's residence is Bhubaneshwar, India's Ham radio operators have been pegging away at keeping the lines of communication going. Between a desperate Chief Minister and the Central government, between district magistrates and the Secretariat at Bhubaneshwar, between anxious families in the rest of the country and their loved ones in the affected districts. The box crackles away all day with updates. "What is the present situation of Jaipur?" asks the volunteer operator in Delhi. "Much better," replies a volunteer at the other end. "Shops are open, electricity has been restored, but not much of telephone lines, drinking water is limited, but it is on."

At the time of writing, telephone lines were still down pretty much all over the State, except in the capital. A sweet shop owner from Kalkaji hovered anxiously around, enquiring on behalf of the Oriya labour he employs as to what the fate of their families might be. A message goes across to the appropriate district. Soon a volunteer is able to report that there has been no human casualty in those localities. That is the best the shop owner can hope for right now. He greatfully goes home.

All the operation takes is a couple of black boxes on a table: one is the trans-receiver, the other the power supply unit (If you are running it on batteries you do not need this). A wire connects the boxes to a horizontal antenna on the roof. Next to the table a notice board has some neatly printed sheets detailing the number of stations in operation, their code, the names of their volunteers. There are 13 high frequency stations operating: at the CM's residence and at the Secretariat at Bhubaneshwar, at the Srikakulam collectorate in Andhra Pradesh, at jagatsinghpur, Jaipur, Paradip, Calcutta, at Erasma, which is the worst affected according to the volunteers, at Delhi and Hyderabad and a few other places. There is also a neatly typed sheet listing the worst affected localities in Cuttack, Bhadrak, Jaipur, Kendrapara and Balasore.

There is a log book filled with entries and scraps of paper that Oriyas in Delhi have left here, with addresses and telephone numbers of those they want information about. The phone numbers are useless but sheer compassion comes to their rescue. In Cuttack a volunteer boards an auto rickshaw clutching a sheaf of requests from other parts of the country, goes from locality to locality checking out the position and comes back with details. In the cities he reports to, other volunteers jot it all down and call up phone numbers of families that have made the requests.

The district administration's dependence on the ham operators is total: they have no other means of communicating with Bhubaneshwar. Particularly their dependence on those who operate the Very High Frequency (VHF) stations which covers arears spread across the affected districts, Deepak, who is conveying information from Jaipur, says that he is a volunteer from the Orissa Disaster Mitigation Mission. Many of the volunteers are from Hyderabad and Calcutta. What do you do, you ask shared from Andhra Pradesh whose voice comes through loud and clear from Gridhar Gamang's residence. "I am the director of a software company," he replies. he has left home and work to put his hobbyist skills to human use.

The nucleus of the ham radio fraternity is the National Institute of Amateur Radio (NIAR) at somajiguda, Hyderabad. They came into existence in 1975 and were able to do their bit for the Andhra cyclone in 1977. It is a scientific hobby, says Bharathi Prasad, Additional Director of NIAR, who is now in Delhi promoting its activities in North India. There are 20,000 radio hams all over India, that they have been given training by organisations like hers, and operating licences by the Ministry of Communications. It is a medium you do not hear too much about, but one you cannot do without when the worst calamities occur.

Author - Sevanti Ninan

How the Ham rescue operation

started in Orissa?

Ham radio has once again proved its utility when the hotline from the Orissa Chief Minister's residence to the nation's capital broke down during the month of October/November 1999. Government of Orissa had to request the ham radio operators to set up communication link between Orissa Bhawan, New Delhi and the Orissa Chief Minister's Residence during the devastating cyclone. For more than a month, communication link within and outside the state of Orissa was maintained through ham radio only.

Orissa

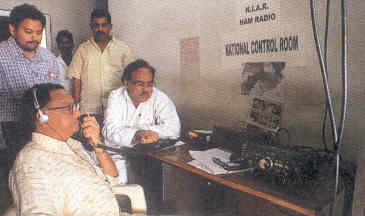

Chief Minister Giridhar Gamang operating a ham radio station set up by a

|

As per a Times of India News Service report (published on November 3, 1999), the process of establishing an emergency ham radio communication network in the cyclone-ravaged Orissa was started by Sri S.K. Nanda, Managing Director of Gujarat State Finance Corporation (GSFC) and an Oriya IAS officer on October 30, when the first reports of cyclone devastation started trickling in, Mr. Nanda failed to contact his family in Orissa. |

A news item published in Deccan Chronicle (Hyderabad Edition).

Sunday, December 5, 1999

When Nothing Worked, HAM Did

When all channels of Communications failed after the cyclone hit Orissa, Ham operators from Hyderabad were the first ones to establish contact with the survivors. K.J. JACOB meet some Hams who have just returned.

October 31, 12 midnight, Orissa Chief Minister's residence, Bhubaneswar. Giridhar Gamang is sitting in the midst of every possible modern communication equipment.... telephones, cellphones, wireless sets. But all dead, like the victims of the supercyclone in the devastated villages. Even that fabled satellite telephone, provided by Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister N.Chandrababu Naidu, is of no use as the battery ran out after a few calls and nobody knew how to recharge the battery with the small generator.

For S.B. Ram, leading a contingent of 20 Ham volunteers from the National Institute of Amateur Radio, Hyderabad, there is no time to lose. He has rushed from Visakhapatnam in a jeep braving cyclonic winds, with wireless sets to set up the communication network that will serve as Orissa's only connection with the world.

Ham is an acronym for amateur radio operators who pursue a two way communication as a hobby . Because of the Potency, amateur radio, like all amateur radio services, has to be regulated on an international basis.

The regulating body, the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), is based in Geneva, which is an agency of the United Nations Organisation.

After 48 hours of chilling, unbearable silence from Orissa, the first words that the outside world heard was from Gamang, detailing the magnitude of death and destruction on the network set up by the Ham operators.

Within a few hours, the Ham operators set up stations at Kalinga Stadium (Control room for the movement of relief material), Capital Hospital (medical teams) and the airport (airdropping of food materials).

"The Secretariat was in utter chaos. With no means of communication, nobody knew what was happening. Decision-making was the last thing happening at the nerve centre of the State administration when it was needed most. Bureaucrats would rush around trying to meet officials, only to be told that they had left to meet another person," recalls Ram.

Ham Volunteers knew the importance of communication and its vital place in rapid decision making. Their experience during relief operations during calamities like the Diviseema cyclone of 1977, the 1990 Machilipatnam cyclone, the Latur eqrthquake made them act fast.

Senior officers manning crucial departments including the Chief Secretary and the Special Relief Commissioner were given handsets so that they could stay in touch with officials coordinating relief operations in remote districts.

The Ham operators were helping not jus the officials who were grounded without communication; they were setting up a vital link for the thousands of the people rendered homeless by the cyclonic tidal waves and screaming for help without food and even water.

On November 2 morning, teams fanned into districts with senior officials and setup several stations at Jagatsinghpura, Erasma, Badrak, Kendrapara, Jaipore. There was also a mobile station which would move around to cater to the requirements of the other stations.

They would carry a high - frequency station, a very high frequency station, 2 VHF hand-held walkie-talkie sets, antenna wire, a power supply wire and log book to record the communications.

They would set station and collect the details of death and devastation with the help of such local officials who had not fled.

The messages would be passed on either to the district headquarters or the State capital. For relief, they contacted the relief control rooms directly.

The on-site officials would use the Ham network to contact the control room in charge at Kalinga Stadium on the requirements for food, clothing etc. They would in turn relay the details of relief materials despatched. Requirements of doctors, paramedics, medicines, bleaching powder etc., could be communcated to the Capital Hospital. The airport control room would be informed about the locations where food packets needed to be air-dropped by Indian Air Force helicopters and in what quantity.

"We told the villagers to go to high spots and wave red sarees. The helicopter pilots were instructed to spot the signal and drop packets there. This would minimise the loss of food stock," says Ram

Proper and and reliable communication provided in time could optimise the relief operation and avoid waste of manpower, material and time "At first, the helicopters dropped just rice bags. But there was no point in giving the people rice with nothing else - not even clean water we suggested that the packets have atukulu, sweet, biscuits, water sachets.... basically ready - to - eat food," tells S Ram Mohan a soft ware engineer who operated the Ham station in Badrak.

The outbreak of cholera at some places could be checked as medical teams were rushed immediately after being informed in the net work. "The first message of Jagatsinghpura Collector was to 'send 200 doctors who are prepared to work under any conditions. They will have to fend for themselves... they will carry their own food water and tent material. We passed thousands of such messages, "says Sushil Kumar Dhingra who worked in the worst-affected Ersama block , which accounted officially, for over 8,000 deaths.

Amidst such destruction, stood Nandagopal Das' concrete house, untouched by the cyclone. The tank in his house continued to have pure drinking water. Das made no secret of this and distributed the water among the needy. And that too in cupsful.

"For the first six days, there was no rest. We would leave in the morning from Jagatsinghpur for Ersama. We dared not touch anything available locally. We survived only on biscuits. On return, we would sleep in the Collector's office, the only place with a generator. We also needed electricity to recharge our battries."

The whole of Orissa, including the Chief Minister, the Chief Secretary, Collectors, Officials and the Common People were all praise for the work the Andhra Pradesh team had done.

NIAR has sent another team of six volunteers to Orissa on November 30. While saying that they are satisfied with what they did, they pointed out that much more could have been done had the authorities paid a little more attention to the simple means of communication.

" In the entire State of Orissa, there are just two Ham operators. If they had at least one in every village, help would have been instant and more effective, "says P Anil Kumar, Ham volunteer and photographer.

Things may change for the better. Talks are on with the Grid Corporation of Orissa, which evinced keen interest in supporting the network, to train at least one operator in every division.